The basis of Murphy's Law is that no matter how idiot-proof something is, there will always be an idiot who rises to the challenge. Murphy's Law today seems like an ages-old axiom. We know it today as, "Whatever can go wrong, will go wrong." The truth is that it's not ages old, and only dates back to the Cold War-era U.S. Air Force.

In the late 1940s, the Air Force was in the age of the test pilot: pushing the limits of where aviation technology could go, how fast it could get there and what effects it would have on a human body. Luckily, no one died in the creation of Murphy's Law.

In 1948, the Air Force was working on a research project at Edwards Air Force Base, California, codenamed MX981. The purpose was to find out the effects of gravitational acceleration (G-forces) on fighter pilots. They believed the maximum G-forces the human body could withstand was 18. They would soon discover they were wrong, but they needed to do a number of tests to find out.

One of those tests involved a rocket sled, attached to a 1.9-mile rail track in the middle of the California desert, one capable of supersonic speed. They wanted to propel the sled to speeds of at least 200 mph and then hit the brakes to stop the sled in less than a second. The idea was to test the effects of intense flight and crashes on humans.

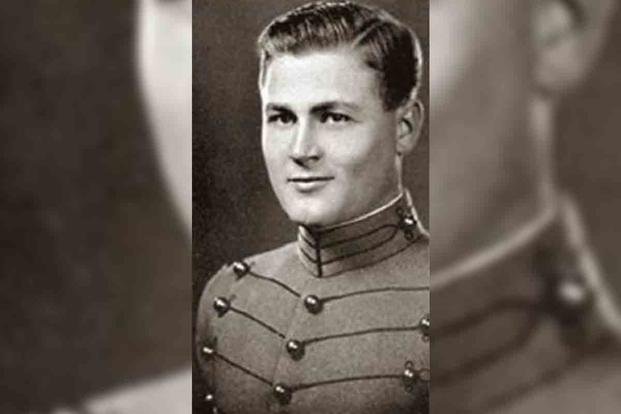

Their rocket sled was nicknamed "Gee Whiz," and the team of data collectors on a particular experiment in 1949 was led by Capt. Edward Murphy. Murphy was a West Point graduate and World War II veteran who served in the China, India, Burma Theater before becoming the research and development officer at Wright Air Development Center of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio.

According to the book "Sonic Wind: The Story of John Paul Stapp and How a Renegade Doctor Became the Fastest Man on Earth," Murphy assigned an assistant to wire four electronic strain gauges, called transducers, to the shoulder straps to measure the G-forces on various parts of the body. The transducers had been constructed at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base for this specific purpose.

When the experiment was run, all of the sensors came back with zero readings. No data. All four transducers had failed. When the team went to look at what went wrong with the gauges, they discovered that each of them had been wired backward, and the electronic signals all ran backward.

They had been constructed incorrectly when they were first built in Dayton, Ohio. Capt. Murphy, disgusted at the lack of attention to detail, said, "If there's any way these guys can do it wrong, they will." Murphy then had to hand-carry the gauges back to Dayton.

Lt. Col. John Stapp, the overall commander of the MX981 project, was soon asked by a reporter how they managed to avoid any injuries or fatalities with a project like his. Stapp told the reporter that his crew operated under "Murphy's Law, if anything can go wrong, it will." He was trying to tell the reporter that the Air Force anticipated possible failures, assuming a worst-case scenario, and to address those possibilities before anyone got hurt.

For Stapp, it was just one more law he'd coined while working on aerospace tests. His most well-known before Murphy's Law was "Stapp's Law," which partially echoed Murphy's sentiment: "The universal aptitude for ineptitude makes any human accomplishment an incredible miracle."

Stapp hadn't coined Murphy's Law, but he was instrumental in making it a popular expression. Murphy's Law was eventually engraved on a plaque at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point and soon eclipsed the entire MX981 test program. To refocus the effort, Stapp began testing again.

By Christmas 1949, the test program had graduated from using crash test dummies and even chimpanzees to test the effects of G-forces. With Murphy's Law guiding their research, Stapp became the human test subject, enduring 35 Gs of force, facing both backward and forward. The press soon nicknamed Stapp as both the "fastest man on earth" and the "bravest man in the Air Force."

-- Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.