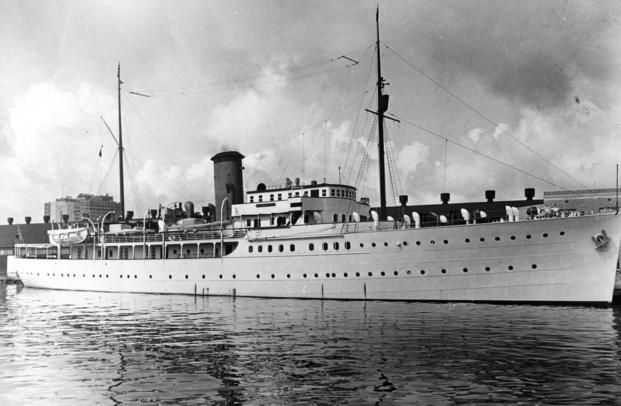

Vincent Astor's yacht, the Nourmahal, was among the largest private boats on the seas. Partly financed by the more than $300,000 profits realized from his investment in the 1926 film version of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, the 263-foot ship was over-the-top in both luxury and technology for its time. It was built by the Krupp Iron Works, which would later turn out U-boats, in Kiel, Germany,

Astor occasionally used the Nourmahal (Persian for “light of the palace”—or, more playfully, “harem’) to host monthly meetings of “The Room,” a small, tightly knit group of powerful, well-connected men —no women—who met in secret to share intelligence garnered from New York’s social whirl, travel, and business dealings. With 11 state rooms and a crew of more than 40, the “Nourmy,” as Astor’s guests called it, also sometimes hosted his friend, patron and, beginning in 1933, President of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Not all the cruises were social, however. In 1938 Astor and Kermit Roosevelt, Theodore Roosevelt’s son, undertook a reconnaissance mission under cover of scientific expedition to surveil Japan’s military activity on the Marshall Islands. Outfitted with a radio on loan from the U.S. Navy, they were to report on things like docks, fuel depots, and airstrips.

Astor seemed nearly giddy on the eve of his spy mission.

“I don’t want to make you jealous, but aren’t you a bit envious of my trip?” he wrote the president. “My deportment in the Marshalls will be perfect,” he went on. “When and if, however, there is something that deserves taking a chance—or if I notice increasing suspicion or resentment, I would like to be able to send a ‘standby’ message to Samoa or Hawaii.” The emergency signal would be the word, “automobile.”

The mission, not altogether successful, did yield some intelligence, according to ONI historian Jeffery M. Dorwart. Although unable to get close enough to the targets for visual accounts, Astor intercepted radio signals from Eniwetok Atoll confirming it as a principal Japanese naval base and Bikini a secondary.

Conversations with British officials supplemented his reports. It would be among the last of the long voyagers for Astor on the Nourmahal. Like his previous yacht, the Noma, the ship would see service in the war effort, commissioned into the fleet of the U.S. Coast Guard in 1940, then the U.S. Navy in 1942.

When the State Department got wind of Astor’s back channel arrangement, the flow of intelligence was temporarily halted. It resumed with the 1940 arrival of William Stephenson (famously known as Intrepid), head of the British Security Coordination (BSC), and his American-born wife, Mary. Astor personally invited Stephenson to lodge at the St. Regis, the luxurious and technically advanced hotel—telephones in every room and an early version of air conditioning— founded in 1904 by his father, John Jacob Astor IV, one of the richest men of his time, who had died in the 1912 sinking of the Titanic. The invitation, puckishly derided the luxury hotel as a “broken down boarding house.”

Despite the anodyne name, the British Security Coordination would eventually grow into one of the largest and wide-ranging clandestine intelligence operations of the war. With FDR’s secret approval, the BSC was going to help nudge Americans into supporting Britain’s desperate defiance of the Nazis. Stephenson’s aggressively vague remit allowed him to launch operations that ranged from traditional intelligence-gathering via secretly recruited agents to highly creative black propaganda efforts. Among the BSC operations Stephenson oversaw were honey traps, safe-cracking in embassies, planting stories in the press, and even a high-profile publicity tour by an astrologer who predicted American victory in the war.

On February 4, 1941, Stephenson wired back to London, “President has appointed Vincent Astor as his personal liaison with me…This arrangement is a great step forward and should considerably facilitate our efforts…”

It was through Astor that London gained a reliable and secure source to contact the president directly regarding matters that could not properly be transmitted through formal diplomatic channels.

Among the items Stephenson transmitted through Astor was a top secret report on Vichy French activities in the U.S., obtained by bugging the New York office of Jean Louis Musa, a naturalized American who supervised the activities of the Vichy Gestapo. This was not a new approach by British intelligence. During WWI, a British banker-spy in Manhattan, Sir William Wiseman, had established a very similar line of communication with President Wilson via trusted presidential adviser Col. Edward House.

The gentlemanly espionage of The Room, however, with Astor comfortably operating among his well-heeled peers, was coming to an end, along with the free-wheeling days of the gentleman spy answerable only to the president. With America’s entry into the war following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the men of The Room were scattered among government agencies and wartime industries. William Donovan went on to head up the OSS, while David K.E. Bruce oversaw the European branch of the OSS in London. Allen Dulles, a future head of the CIA, would also enter the service under Donovan’s OSS in Switzerland.

Manhattan Transfer

In April 1941, Astor was appointed “Area Controller for the New York Area.” The specified responsibilities were “coordination” of “intelligence and investigational activities in the New York area undertaken by representatives of the Departments of State, Navy, War and Justice.” Astor, who held the Navy Reserve rank of commander, was authorized to “act as a clearing house for problems” and incoming intelligence in New York. Whether he was auditioning for a top spot in America’s nascent intelligence effort is not known, though he was soon beset by rivals and discovered himself unsuited to the rough and tumble politics of inter-agency bureaucratic combat.

At a time when control over intelligence operations seemed up for grabs, there was no shortage of competitors among both seasoned professionals like J. Edgar Hoover and Donovan, as well as ambitious amateurs, such as the newspaper columnist and author John Franklin Carter, who ran a boutique spy agency for the president.

“Carter may be the only writer who first created a fictional intelligence agency and then persuaded a government to put him in charge of a real organization modeled on it,” according to Steve Usdin, author of Bureau of Spies: The Secret Connections Between Journalism and Espionage in Washington, writing in the CIA’s in-house journal, Studies in Intelligence.

Bureaucratic hassles were also not in short supply. For instance, OSS chief Donovan found himself in direct conflict with Hoover and the FBI as well as some truly unexpected adversaries. At one point, Ruth Shipley, ensconced in the Passport Division of the Department of State, refused to provide passports to Donovan’s under cover officers without stamping them “OSS,” thereby giving away the game. It took FDR’s presidential intervention to force Shipley, likely a Hoover loyalist, to finally relent.

In another instance, Donovan fended off the Washington, D.C. police department and Interior Secretary Harold Ickes when an OSS courier was pulled over for zooming across the Arlington Memorial Bridge at the breakneck speed of 50 mph to deliver film to a waiting plane. Ickes deemed the speeding “reprehensible.” Unlike Astor, Donovan seemed to relish the fight. “I have greater enemies in Washington than Hitller in Europe,” he quipped to his assistant Fisher Howe.

Things were no better at ONI for Astor. Although he tackled the assignment with enthusiasm, internal correspondence wrote him and his position off as a “make work” project for a friend of the president. “Astor must have a job…,” one internal memo read. “Vincent Astor, for your information, stands very close to the great white father, so proceed with caution.” This attitude, though somewhat inaccurate, is understandable given that Astor reported directly to FDR. But what today would be called “compartmented” activity worked against Astor’s in-house reputation. The secret nature of his clandestine activities made it appear as if he had done very little, when, in fact, he had been quite busy.

One operation in particular seemed to cause him consternation. An overseas network run by a shady character offended Astor’s fiduciary sensibility with its seemingly unlimited budget, but almost as offensive was the spymaster running the operation. He was, in Astor’s opinion, not only indiscreet, but also a “social climber.” Espionage has always involved the cash-and-carry cooperation of less than gentlemanly characters, but what comes across in a letter delivered by messenger to FDR, was genuine shock at the ungentlemanly nature of the individual involved.

Someone also leaked Astor’s role as FDR’s private spy, diminishing his effectiveness in the role. A confidential report on Astor requested by the president did nothing to help his cause. Increasingly marginalized, Astor focused on coordinating civilian boats, such as fishing trawlers, to patrol the eastern seaboard and establish defenses against U-Boats along the East Coast. Ill health eventually curtailed his duties, and in 1944 he officially resigned the post.

By then, Donovan had long been established in the top spot of the OSS. Hoover was somewhat appeased with suzerainty over domestic efforts against spies and saboteurs and a slice of the foreign espionage pie in South America.

If Astor’s wartime duty as a spy was minimal, he remained significant by providing an infrastructure in which both British and American spies could operate throughout the conflict. As something akin to a quartermaster, not only did he loan out the Nourmy to the war effort, his properties were freely made available to Anglo-American intelligence efforts as needed. The St. Regis became something of a spy hub, too, so impressing the young Naval intelligence officer Ian Fleming during a May 1941 stay with his superior, Admiral John Henry Godfrey, that he wrote the hotel into a Bond adventure. In Live and Let Die (1954) Fleming describes the St. Regis as “the best hotel in New York,” and Bond meets his CIA contact, Felix Leiter, in the hotel’s King Cole Bar. Double-0-7 would later stay at the Astor Hotel, another family property, in Diamonds are Forever (1956).

It was also in a St. Regis suite that Stephenson persuaded Wall Street lawyer and World War I hero Donovan to undertake a fact-finding trip to besieged England. Donovan, whose organization of the fledgling OSS is said to have been influenced in part by suggestions passed along by Godfrey and Fleming, later presented James Bond’s creator with a .38 Police Positive revolver inscribed “For Special Services.”

And, for a brief period of time, the OSS was run out of the St. Regis. In early April of 1942, after suffering a car crash in Washington, Donovan had himself carried aboard a train to New York to attend a scheduled meeting at the swanky hotel. Deposited in a two-room suite, he soon learned that not only was his leg broken, but a blood clot had traveled to his lung causing a dangerous embolism. For the next six weeks the spy chief remained ensconced in the suite, receiving official visits, dictating letters and memorandum and talking on the phone. “I’m still in the ring,” he reported to friends.

In addition to the St. Regis, Astor made other properties available for intelligence work. At a Times Square property, he provided space for a company calling itself Diesel Research. An FBI front company headed by double agent John Sebold, Diesel’s sixth-floor office space included a hidden compartment from which FBI agents filmed activities of what the Abwehr believed was their own clandestine communications operation. For nearly two years, the German-born Sebold, a naturalized American citizen, posed as an operative in a German spy ring led by a South African-born Nazi agent, Joubert “Fritz” Duquesne.

Sebold and Diesel Research would prove one of the FBI’s most successful operations. In 1941 the Bureau rolled up the Duquesne Spy Ring, leading to 33 convictions of Abwehr operatives. The case inspired an Academy Award-winning 1945 Hollywood film, The House on 92nd Street, featuring cameos by multiple FBI special agents as well as Hoover himself.

Astor had also bought a floundering magazine known as News-week (soon to become Newsweek) and allowed both British SIS officers and the FBI to use the magazine as cover for overseas assignments.

Patrician Tact

As with many citizen spies who served America’s intelligence efforts, Astor did not pursue or receive public recognition or private payment for his clandestine efforts. Although some writers mischaracterize his espionage activity as a rich man’s folly, both public and private documents indicate he took the work seriously and made significant contributions. However, the war’s end signaled the emergence of a new conflict—the Cold War—and new, more professional, intelligence organizations required to counter the threat.

According to credible accounts, Astor turned gloomy in his later years. His third marriage, this one to Brooke Russell, a former long time mistress whom he had once pursued with love letters, gifts of expensive jewelry, and introductions to glamorous acquaintances, had turned sour.

With his health increasingly failing, Astor began drinking more heavily, became something of a recluse, and curtailed his wife’s once active social life. Reports of Astor, particularly during his last years, remain somewhat contradictory, depending on what side of the inheritance the observer eventually landed on.

The presence of the enormous fortune that burdened him early on continued to prove a central fact of his life. He is said to have taken up the hobby of re-writing his will, sending repeated shockwaves through the family. There was, according to reports, much speculation over who would get what, and how much. An adult case of mumps had, reportedly, precluded heirs.

But for anyone who had paid close attention to his life , there need not have been much of a mystery. When Astor died in 1959 of a heart attack in his Manhattan apartment on East End Avenue at age 67, he left more than enough to provide for his widow. The bulk of his estate, however—estimated at $40 million—went to the Vincent Astor Foundation, “dedicated to the alleviation of human misery.”

Newspapers around the world noted his death, though even the most elaborate obituaries made scant mention of his espionage efforts. As to be expected, all of them invariably made much of the enormous fortune he left behind. As a spy, he remained largely a ghost. ###

New SpyTalk contributor Henry R. Schlesinger is an author and journalist who has been writing about things espionage for more than two decades. His most recent book is Honey Trapped: Sex, Betrayal, and Weaponized Love.

This article first appeared on Spytalk.co.