Joseph V. Micallef is a best-selling military history and world affairs author, and keynote speaker. Follow him on Twitter @JosephVMicallef

The political constellation of the Middle East has been, until recently, relatively durable for the better part of three-quarters of a century. Except for the division of the British mandate of Palestine between Israel and Palestine and the border revisions precipitated by four subsequent wars, the rest of the region largely adhered to its World War II-era frontiers. True, there was no shortage of additional conflicts, some of which did result in minor border revisions, but their impact on the overall political geography was minor.

In June 2014, after successfully expelling Iraqi military forces and seizing control of large portions of Anbar, Nineveh, Kirkuk and Salah al-Din provinces, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi proclaimed the birth of Islamic State (IS) comprised of the regions in Syria and Iraq under his control. Al-Baghdadi also proclaimed himself caliph of IS, simultaneously declaring himself the supreme political, religious and military leader not only of the roughly six million inhabitants of the world's newest political state, but of the one and a half billion Sunni Muslims worldwide.

In making the announcement al-Baghdadi also famously announced the abrogation of the Sykes-Picot Treaty, highlighting an agreement long forgotten by everyone save for historians and the odd diplomat. He followed up his announcement by ordering the filling in of the moats that had previously marked the desert border between Syria and Iraq.

This symbolic erasure of the national frontiers -- and by extension of the nations that they defined -- that had resulted from the imposition of Sykes-Picot was a declaration that the contemporary nation states of the Middle East lacked legitimacy. There governments therefore were equally illegitimate. Per al-Baghdadi, it was the duty of every good Muslim to oppose those governments. Only the Islamic State and its restored caliphate was the true expression of the political and religious unity of the Muslim world.

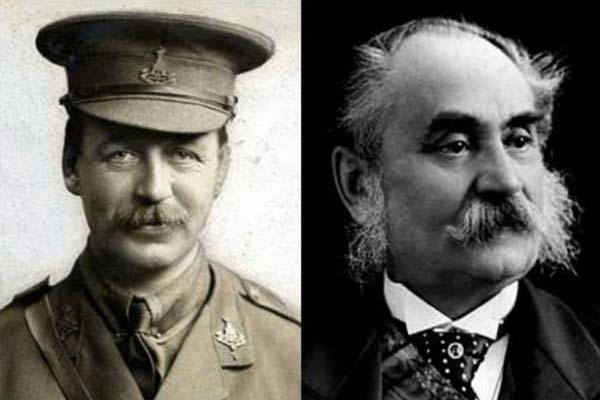

Sykes-Picot had a rather convoluted history. Technically, it was called the Asia Minor Agreement. It was negotiated by a British diplomat named Mark Sykes and a French diplomat named Francois Georges-Picot, hence its name. Its roots lay in the entry of the Ottoman Empire into WW I.

On October 31, 1914, renegade elements within the Ottoman military, most likely with the compliance of German advisors, staged a raid on the Russian naval base at Sevastopol. The raid was led by two former German ships, the heavy cruiser Goeben and the light cruiser Breslau, which had recently been gifted to the Ottoman navy by the German government. The original German crew and officers had remained, now wearing Ottoman uniforms and ostensibly part of the Ottoman Navy.

The raid had occurred against the express wished of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed V, who had insisted that the Ottoman Empire remain neutral in WWI. Following the raid, Mehmed V repudiated the attack calling the attackers renegades acting without the authority of his government and offering to pay reparations to the Russian government for any damage done.

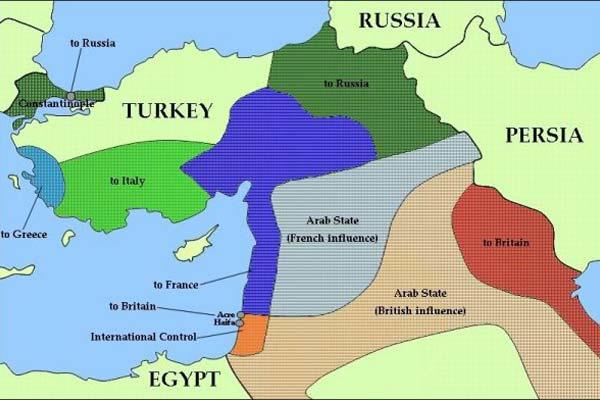

Russia, looking for an excuse to attack the Ottoman Empire, rejected the offer and promptly declared war. Russia demanded that its British and French allies accept Russian control of Constantinople and large portions of the Black Sea coast and, most importantly, Russian control of the Turkish Straits and portions of the surrounding coastline. Reeling at the time from the German onslaught on the Western Front, (the First Battle of the Marne was barely a month old) Great Britain and France had little choice but to agree.

Subsequently, with the consent of the Russian government, Great Britain and France developed a plan for the partition of the rest of the Ottoman Empire. This was the genesis of what would become the Sykes-Picot treaty.

After the war ended, Lenin insisted that the allies honor the terms of their original agreement with Russia. The Allies refused claiming that the Bolsheviks had forfeited their territorial claims when they had signed a separate peace with the Central Powers at Brest Litovsk. Lenin, incensed, ordered Pravda to publish the text of the Sykes-Picot agreement (the Russians had been furnished a copy). That's how the world subsequently learned of how Britain and France were planning to carve up the Ottoman Empire.

Sykes-Picot was the first, but not the only treaty that would subsequently define the political topography of the Middle East. Two, in particular, concerns us today, because they appear to be the next WWI-era agreements about to be cast aside; the Treaties of Lausanne and Ankara that, among other things, defined the national frontiers of modern Turkey.

Shortly after the onset of WWI, Britain had landed troops in southern Mesopotamia and seized control of the Shatt al-Arab and the city of Basra. The attack was ostensibly to protect the flank of the oil fields recently discovered by the Anglo-Persian Oil Company and the refinery at Abadan. That refinery was the Royal Navy's principal source of fuel oil.

Later, British forces were ordered to march on Baghdad, as a show of British military power to the Empire's Muslim subjects. Enver Pasha, the Ottoman Minister for War, had been trying to incite Muslims in the British and Russian empires to revolt and declare a jihad against their colonial masters.

British interest in Mesopotamia was also prompted by another consideration. Russian success against Ottoman troops in Eastern Anatolia had opened the prospect of Russia seizing control of Mosul. The region around Mosul was believed to hold significant oil deposits as evidenced by numerous petroleum seeps. Oil was subsequently discovered there in 1927.

The first march on Baghdad ended badly, with the British Army suffering, at the Siege of Kut, its worse humiliation in half a century. The subsequent campaign fared better and British forces steadily advanced northward, seizing Baghdad on March 11, 1917 and continuing to advance up the Tigris valley.

Hostilities between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies were supposed to end on October 31, 1918 when the terms of the Armistice of Mudros went into effect. Per the Armistice, both sides were to hold their positions as of October 31 pending a formal peace treaty that was to follow.

The War Office in London however, instructed the British Commander in Mesopotamia, General William Raine Marshall, "to make every effort to score as heavily on the Tigris before the whistle blew," so notwithstanding the terms of the Mudros armistice, British forces under General Alexander Cobb continued to advance northward till November 14.

The last battle fought between British and Ottoman forces had been at al-Shirqat, 65 miles south of Mosul, on October 25. Had London observed the terms of the Mudros armistice, that would today have been the northern frontier of Iraq. Kurdistan as well as Mosul and much of Nineveh and northern Salah al-Din province would have remained part of the Turkish Republic that would subsequently emerge post WW I.

Northern Iraq had never been part of historic Mesopotamia. Its traditional population had been predominantly Kurdish, Turkoman and Christian. Prompted by its suspected oil wealth however, Great Britain bolted the region to its mandate of Mesopotamia that would subsequently be organized under League of Nations auspices.

Ironically, in the Sykes Picot agreement, that portion of the Ottoman Empire had been slated to become part of the French mandate of Syria. Great Britain hung on to it however, and instead agreed that the French government could seize the 25% interest in the Turkish Petroleum Company owned by the German government in compensation.

Which brings us to the present day and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan's insistence on a role for the Turkish military in the liberation of Mosul. On December 3, 2015, Ankara deployed a detachment of 150 Turkish soldiers and 25 tanks to the Iraqi town of Bashiqa, 10 miles north of Mosul. Ostensibly, they were there to train the Hashd al-Watani, the local Sunni militia and to assist Kurdish Peshmerga forces. The Turkish force was subsequently increased to battalion strength, now numbering about 600.

In addition, Iraqi sources claim that there are at least 1,500 more Turkish troops deployed in Northern Iraq conducting counterinsurgency operations against the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). The presence of Turkish troops in Iraq, a blatant violation of Iraqi sovereignty, has precipitated strident protests from Baghdad and anti-Turkish demonstrations from various Shia militias.

On October 30, in response to the deployment of al-Hashd al-Shaabi Shite militias west of Mosul, Turkey moved an unspecified number of troops to Silopi along its border with Iraq and warned those militias to not attack the IS held town of Tal Afar or any of the surrounding villages. The area has a large Sunni Turkoman population which Erdogan has vowed to protect.

The Turkish government has stopped short of abrogating the treaties of Sevres and Ankara which defined Turkey's borders. On the other hand, in what amounts to a de facto abrogation, Erdogan has insisted that "Mosul is ours" and that "Mosul is Turkish." Erdogan has also resurrected the "National Covenant", a 1920 declaration by the last Parliament of the Ottoman Empire that reaffirmed that Northern Iraq was an integral part of Turkey and which identified a broad surrounding area from Cyprus to Aleppo to Batum as belonging to the Turkish state.

Erdogan has asserted that Ankara had a right to a Turkish sphere of influence over the region that once made up the Ottoman Empire, noting that "Turkey bears also responsibility towards the hundreds of millions of brothers in the geographical area to whom we are connected through our historical and cultural ties." He went on to add. "It is a duty, but also a right of Turkey to be interested in Iraq, Syria, Libya, Crimea … and other sister areas"

What exactly are Ankara's objectives here? Does Erdogan harbor any fantasy that Mosul and its surrounding region is somehow going to be returned to Turkey? That's not going to happen short of a war between Turkey and Iraq.

Is Erdogan looking for a seat at the negotiating table and some chips with which to play? If so, to what end? A piece of Mosul's oil wealth, a Turkish sponsored and protected Sunni state from a sectarian division of Nineveh province or simply some role in the subsequent political organization of Northern Iraq? Is this an attempt at political grandstanding for supporters back home, a gambit to preclude safe havens for the PKK, or is Ankara serious about developing its own, anti-Iranian/anti-Shia arc of influence in the region of the historic Ottoman Empire?

Western media typically portrays the "Kurds" as a single entity. There are deep divisions within the Kurdish community however, not only among Iraqi Kurds but especially between the Kurdish government in Erbil and the PKK. Ankara has attempted to develop close ties with Iraqi Kurdistan while being vehemently opposed to the creation of a PKK sponsored Kurdish state in Syria.

Turkish air forces have been attacking the predominantly Kurdish, Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Syria while at the same time Turkish artillery has been supporting the advance of Kurdish Peshmerga troops against IS controlled territory north of Mosul. Moreover, notwithstanding the bitter, historic rivalry between the PKK and Iraqi Kurds, Erbil, to Ankara's displeasure, has granted safe havens to the PKK.

There is a larger issue here however that goes beyond the Battle for Mosul. Turkey is increasingly behaving like a rogue actor in the Middle East; showing ambivalence about respecting the historic basis of the status quo and demonstrating a willingness to act unilaterally with military force to change that status quo or at the very least mold it more to its liking. That is a role that will bring Ankara into conflict with Washington and one that is incompatible with a large role for Turkey in the European Union.

Ironically, Erdogan's desire to develop a "Turkish sphere of influence" in the Middle East, to counter the "Iranian/Shia arc of influence" that now stretches from Tehran through Baghdad, Damascus, Beirut and Gaza could, under the right circumstances, be in America's interest. Erdogan's insistence of going it alone and on framing that policy in increasingly Islamist and anti-American terms, however, makes it problematic for the United States.

Turkey's role in the Syrian conflict is already at odds with NATO's objectives in the region. Ankara's air attacks against the SDF, the principal American proxy in the ground war against the Islamic State, is also incompatible with American interests in the area.

Even more disturbing, is that such attacks could not have occurred without Russian compliance. That means that for all practical purposes Ankara and Moscow are teaming up to attack an American proxy force in Syria. Strange behavior from a NATO ally; especially one that has received billions of dollars in American military assistance over the years.

That does not mean that Turkey will leave NATO or that the US will lose access to its Turkish facilities. It may well suit Erdogan to maintain that illusion of normalcy in its relations with the United States and Europe. It does mean however, that the appearance of cooperation is just that, an illusion, and that, it is likely, Turkey will move too continue to restrict what operations the US can conduct from Incirlik while continuing to pursue a "go it alone" regional policy that is fundamentally incompatible with American and NATO's objectives in the area.

The expression "the enemy of my enemy is my friend" has often been used to describe the Byzantine nature of Middle East politics. For the United States, however, it seems that in the Middle East even its friends act like its enemies. Time for a serious rethink of US policy in the region and how it is being conducted.