Officer candidate Sylvester Benjamin Butler's letter to his mother:

Plattsburgh, N.Y.

June 3, 1917

Dear Mother,

I'm writing this afternoon from the Y.M.C.A., which is a considerable improvement over the bunk. And I notice, too, that there is plenty of reading matter here, which I believe you asked about once.

The week has seemed shorter than the earlier ones, probably because of the holiday we had Wednesday. We have had drill in marching movements two hours every morning except Friday, and Tuesday when it rained so hard. More of our drill is now in formations at the firing line -- how to deploy from the column of march into the skirmish (firing) line (called extended order drill) and how to advance the firing line during engagements.

The drill before this week has been more of what is known as close order drill -- marching movements used when not under fire; and we still have almost half the work in this close order drill. We have had the usual half hour of physical drill every morning, and a half hour of bayonet drill.

The last hour and a half of the morning & afternoon have been as before, conference and study periods. We are surely getting crowded to the limit on this theoretical work; I wrote Eva that when I got back to teaching, I was never going to have any more mercy, or worry as to whether lessons I assigned were too long or hard, and that when students objected, I should have as a byword, "Why, when I was at Plattsburg," etc., etc. -- which should silence all but the keen ones who brought up ancient passages about considering the lilies of the field (a reference to the past).

The first hour of each afternoon, we have had signal work, and there are two codes we are working on now; the first code we learned was what is known as the semaphore, in which certain relative stationary positions of the arms indicate certain letters, and as it is based on a system, it wasn't hard to learn, but it takes a great deal of practice to learn to read a message fast.

The new code we have been taking up this week is known as wig-wag (if I referred to the other in my earlier letters as wig-wag, it was a mistake); I should call it a visualization of the International Morse telegraphic code. For instance, A in the telegraphic code is .- (dot-dash) -- in the wig-wag signal, it is inclining a flag [held vertically in front of body] to the right 90 [degrees] and back, and then to the left 90 [degrees] & back.

A dot is going down & up on the right side, and a dash is going down and up on the left. There is a definite number of words we shall have to be able to send and receive in a minute in each code, as part of the qualification for our commissions, and of course, we are trying in our practices gradually to work up to the qualifying mark. We practice this signal work in a large pine grove south of the camp, each squad practicing apart from the rest.

Each squad, beginning this last week, has had to furnish the platoon leaders and guides in the various drills and exercises for one day. The company is divided into four platoons, each one with a leader and next under him a guide; the 1st lieutenant of a company is the leader of the 1st platoon normally, and the 2nd lieutenant, of the 4th platoon; the six sergeants of the company are the other two leaders & the four guides.

Our squad had its turn Friday, and I drew by lot 4th platoon leader for my job. As on Friday we had a two hour's hike instead of morning drill in the close & extended order movements, which made it somewhat easier. But I had to conduct the physical drill and bayonet exercises in the morning, and rifle exercises in the afternoon for the platoon, so had a chance at some experience in giving commands, describing things to be done, in general acting as a leader - which is of course the idea in having all the men in the company, one squad a day, act in the various positions I spoke of.

Last evening there was an entertainment, very enjoyable for the most part, outside Co.5 barracks for the New England regiment. They have a piano in Co.5, which was of course an important part of the entertainment; and there was usually one man from each company who was a good singer or reciter or who had some tricks, or was a good comedian that furnished the entertainment. Between times, the piano furnished music for the whole audience to sing. They expect to have these get-together affairs every Saturday evening, and I guess every one will look forward to them.

Today Tom Beers and I indulged ourselves in a table d'hote dinner down at the New Cumberland, in town, and you can't imagine how wonderful it seemed -- even to the real table, real chairs, real table linen and china. We had chicken soup, roast turkey and roast pork, mashed potatoes, corn, apple charlotte, strawberry shortcake and ice cream.

Anyone can be excused from mess Saturday night and Sunday morning or noon, and so we planned this little party. How ordinary baloney tasted at supper! I hate it anyway, and don't believe I shall ever like either it or frankfurters. I'll have to admit I like beans already, also macaroni, so you see I'm improving some.

I'm afraid that the laundry won't get to you until tomorrow morning, but hope that won't be too late. Don't feel that you must get sweet chocolate and things to send every time; naturally I have enjoyed them very much. But any rule on eats that exists must be very liberal in its interpretation, for men have been getting all sorts of things, even cakes & pies; so if you want to send me some cookies or crullers anytime I guess there is no danger of their being thrown away - even if they weren't having the pies, &c, surely cookies wouldn't be on any different basis than Nabiscos. But don't feel that you must send me anything unless it's convenient, because I guess I'm in no danger of starving.

The shirt didn't seem to have shrunk any.

If by any chance you got a package with honeysuckle from Eva, it was at my request. The honeysuckle vines grow in marvelous profuseness around Hemlock Manor, and I wish I could see them when they were out. Next best to that, I asked Eva earlier in the spring to send some home to me when they were out; and then I was up here and couldn't have them. It occurred to me that you would enjoy a bunch, and I in writing a couple of weeks ago asked her if she would send them, providing they came out in time. I'm afraid it's too early for them, and as she went up to Philadelphia this week, if she hasn't been able to send them, she won't be now. I thought I would speak of it, in the remote chance that you had gotten them. She forgot to tell me whether she had finally been able to or not.

With much love to you & all

Sylvester.

Bio:

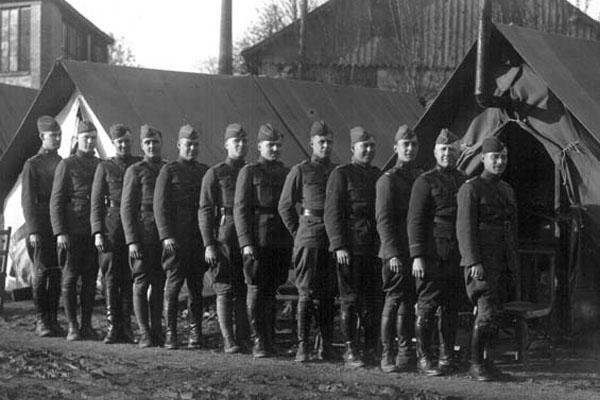

Sylvester Benjamin Butler worked as a high school teacher in Pleasantville, New Jersey. As World War I was heating up, Sylvester joined the officers training corps in Plattsburgh, New York. After receiving his commission, he was stationed at Fort Devens in Ayer, Massachusetts, as an officer in the divisional supply train. In the summer of 1918, he was sent to France, where he continued to send letters until his return home in June of 1919. For more on Butler's war letters and history, visit the Butler family site.

Captain S. B. Butler letters. Copyright 1996, The Butler family of Cromwell, Connecticut.

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.