The United States hasn't officially celebrated the end of a war since the 1991 National Victory Celebration capped off the end of the Gulf War. Before that, Americans celebrated the end of World War II with a massive victory parade down New York City's Fifth Avenue in 1946.

New Yorkers also hosted the nation's World War I victory celebration in 1919. Being part of the winning team in the "War to End All Wars" was a big deal, and the city's Park Avenue was transformed for the event. For a full week, a five-block stretch of one of New York's busiest streets was shut off from the usual din of streetcars, carriages and those newfangled cars to clear a path for Victory Way.

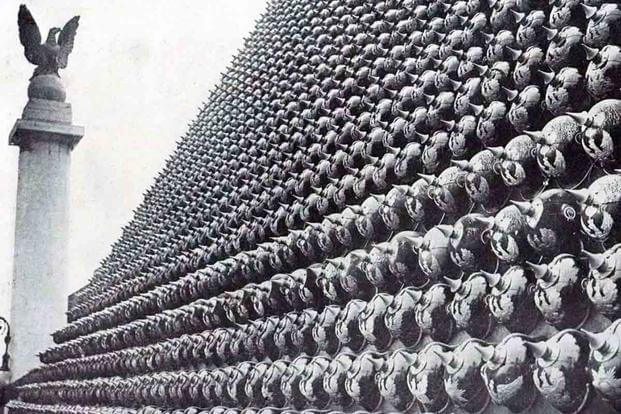

The area was lined with columns and flags, filled with murals depicting the military and industrial efforts of the United States. Between 45th and 50th Streets, the streets, sidewalks and skies were filled with war-related scenes, trophies and honorifics. Marking the end of Victory Way stood a massive pyramid of 85,000 stacked enemy helmets.

It might seem macabre in retrospect, given that every helmet could represent a dead soldier, but the German pickelhaube was a widely known symbol of the enemy throughout the war. With its distinctive spike adorning the top of the helmet, they were used by German armies for decades before Germany became a unified empire.

Propaganda in the United States during World War I frequently and effectively used the image of the pickelhaube to depict the German "Hun" as a bloodthirsty aggressor. It was so effective at representing Germany in propaganda art that it didn't matter that Germany retired the pickelhaube style in 1916, before the U.S. entered the war.

By the time the United States entered World War I in 1917, the enemy's distinctive helmet style was relegated to ceremonial dress for senior German officers. It had been replaced in the field with what would soon become an even more hated symbol of German aggression: the Stahlhelm.

At the war's end, the United States owed $25 billion in war debt. To pay the debt, the government held a series of "Liberty Bond" drives, and the Victory Way celebration in New York was the last of five such drives to crowdsource funds to pay the debt.

Victory Way wasn't just flags, murals and pyramids of enemy helmets. There was an aerial display hanging over the streets, depicting the nature of World War I air combat, simulating real aerial engagements. Below the aircraft, on the ground, was a panorama of Great War battlefields, showing "the whole picture of the war."

While the mock battle raged overhead, floats akin to a parade depicted scenes and imagery from the war. Soldiers showed what it meant to go "over the top" of a trench to assault an enemy position, while other floats recreated important battles and showed how soldiers donned their gas masks.

The spectacle, for the most part, worked as intended. The U.S. government raised 60% of the funds needed to pay down its war debt while citizens invested in a series of $1,000 bonds, all while celebrating an end to the great world war.

-- Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.