For decades after the Civil War, Arizona miners, ranchers and cowboys shared stories of the Red Ghost, a mysterious beast that attacked humans in isolated areas. It was said the ghost was massive, aggressive and carried the pale white bones of its rider strapped to its back.

The story spread until 1893, when a farmer named Mazoo Hastings finally dispatched the creature with a single round from his rifle. The Red Ghost was actually a kind of camel, and its ghostly rider was just a man who was strapped so tightly to the animal that the straps scarred its body.

No one knows who exactly the man was, but the Red Ghost was most likely Army surplus, an escaped leftover from the U.S. Army's failed Camel Corps, an attempt at efficiently exploring and taming the vast expanse of desert that suddenly became part of the United States.

After the Mexican-American War ended in 1848, the United States received 55% of Mexico's territory. Along with the Gadsden Purchase, this set the border at the Rio Grande River and ceded the present-day states of California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, along with parts of Oklahoma, Kansas and Wyoming, to the U.S. It also relinquished Mexican claims to Texas.

This large new territory of more than half a million square miles included massive deserts. The U.S. Army had fewer than 42,000 troops in all to keep more than 100,000 natives in the region at bay. The horse-mounted Army was simply outmatched.

At the time, the Army relied on cavalry for this mission, along with mules for supply trains. This limited the range of the cavalry to areas around known water sources. Meanwhile, the native tribes on their home turf knew about more sources of water and could travel farther and faster without it.

Maj. Henry Wayne saw this problem unfolding even while the U.S. was still at war with Mexico and later suggested to Sen. Jefferson Davis (who was also a Mexican War veteran) that importing camels to be used as supply animals was the solution. Davis agreed, and when he became secretary of war under President Franklin Pierce, he secured the funds needed to try it out.

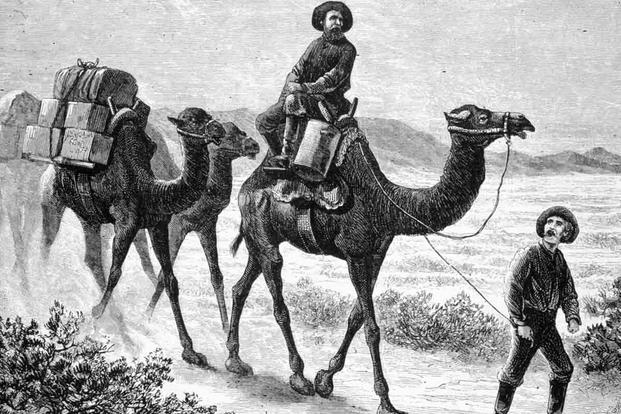

The first joint Army-Navy expedition secured 33 dromedary and Bactrian camels from the Ottoman Empire, which were then shipped in a specially outfitted boat to Indianola, Texas. When it arrived, there were 34 camels, as one had given birth during the voyage to the U.S.

The whole enterprise was so efficient that there was money left over to return to the Middle East and get more camels. By 1857, the second expedition had returned with 41 more camels, bringing the total number of animals in the U.S. Army Camel Corps to 75.

As the Army departed for the second shipment of camels, Maj. Wayne began testing the first shipment of camels for their combat capabilities at Camp Verde, near San Antonio. What began as a hopeful experiment soon looked like a disaster. In short, they were useless in fighting the American way of war.

Camels, it turns out, have trouble breathing while exerting themselves and have a limited lung capacity. They also required a lot more care than horses and mules and didn't really get along with the other animals.

To make matters worse, camels aren't as easygoing as domesticated beasts of burden. They spit, vomit and poop at will, even on their handlers. They are also prone to biting passersby when provoked, even if that provocation is routine discipline.

What they lacked in combat effectiveness, however, they made up for in transportation. The camels carried two to three times as much as a pack mule. When riding with cavalry units, they easily kept pace with the horses, even while carrying a full load of baggage.

Wayne was transferred before the second expedition returned, but before he left, he sent 25 camels on a military survey mission to map a wagon road from Fort Defiance, Arizona, to the Colorado River. This route would take the camels across the driest areas of Texas, New Mexico and Arizona into the Mojave Desert.

The camels performed the mission beautifully and crossed into California by October 1857. They were tested time and again but outperformed mules and horses, exceeding anyone's expectations. The Army wanted to expand the camel program, but the entire experiment was interrupted by the Civil War.

The Union camel company at Fort Tejon, California, was used mainly for local postal routes and not much else. The Confederate Camels, captured at Camp Verde in Texas, were used by some commanding officers, but many were killed by rebel soldiers for being generally unpleasant and hard to get along with.

After the war, any surviving Union camels were auctioned off to circuses, ranchers and farmers. Confederate camels were recaptured by the federal government. Many of these were also sold, but many were simply released into the wild.

Reports of camel sightings near Camp Verde persisted until 1875. One of the lead drivers of the Colorado River expedition, a Ottoman-born citizen named Hadji Ali, purchased some of the camels and established a freight service with them. When that business failed, he released them into the desert, leaving one camel (or its descendant) to become Arizona's famed Red Ghost.

-- Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.