Bio

Born March 17, 1916, near Worms, Germany, Ernest Strauss remembers the difficulties of living in his native country after Germany's crushing defeat in 1918. As harsh as conditions seemed then, they grew far worse for the Jewish Strauss and all of Germany's Jews after Adolf Hitler and the Nazis came to power in 1933. Strauss was one of the lucky ones. He got out before it was too late and came to the United States, where he joined the effort to defeat the Nazis.

Here, Strauss recounts his experiences in his own words.

I grew up in Worms. My dad was serving in the German army in World War I and he was in the trenches. I asked how I was born if he was over there, and he said, "Well, we were gone, but we got furloughs!"

I went to the University of Heidelberg, and I was friends with one of my mathematics professors. One night, I was at his house and he said, "Ernst, I think if I were you, I would leave." I said, "Why?" He proceeded to tell me they were going to expel all Jewish students six weeks afterwards. There were six or seven other Jewish boys in my class and they asked why I was leaving. I told them my father couldn't afford it.

The campaign against the Jews really started in 1934. It was real bad. If you wanted to go to a picture show, you couldn't because it said "Juden Verboten," which means "no Jews allowed." I had a friend working in a shoe factory who was threatened that, if he was seen with me, he would lose his job. He came to me and asked me, "What should I do?" I told him self-preservation. I later found out he was killed on the Eastern front.

In the interim period, some of my family started leaving. I talked about it with my mother and father because I was still not of age. They told me, "No, there's no need; things are changing."

My cousins had left. One went to Czechoslovakia, another went to Paris and finally ended up in Tunisia and came back after the war. The other one went to Uruguay and came up to Cuba and eventually got to the U.S. He had a pretty tough time. Some went to China. They were just scattered.

I asked my relatives if we had family in the U.S.A. I found out we did, and unknown to my parents, I wrote a letter to an uncle in the States. I went to the post office every day so my parents wouldn't see his response. Then came a letter saying, "Come on."

By the end of November 1935, I had all the papers together and took them to the American consulate in Stuttgart. I think by about April, I heard. Visas were on a quota system. My time came up, and I was supposed to appear on May 13, 1936, to get my papers. I left on June 30, went to Bremerhaven and sailed on the Europa.

I arrived in New York, and a group called the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society helped me get settled. When I left Germany, all I could take was 50 marks -- about 20 bucks. My passport still had a big "J" on it.

I spent two nights in New York City. It was overwhelming with all the tall skyscrapers. I couldn't speak the language. I took the Meridian train and got to Monroe, La., on July 9. We were 36 hours on the train.

The uncle who sponsored my arrival in the States was in the wholesale grocery and produce business and the wholesale liquor. I've been in Monroe, La., ever since.

When I first came here they wanted to send me to Louisiana State University. I couldn't understand the language. They put me through the mill.

On Dec. 8, 1941, I wanted to enlist. Went down to the post office. Everything went fine until they asked me, "U.S. citizen?" and the answer was, "No." In order to become an American citizen, you had to reply with your declaration of intention to become an American citizen. I got a lawyer, and he helped me to study for the citizenship exam. I had to learn all the Supreme Court justices, the members of the cabinet. I passed OK.

On Dec. 15, 1941, a week or so after I tried to enlist, I was notified that I was classified as an enemy alien and had to check in once a month. That didn't help my disposition.

They told me that I would have to wait for the draft. I was interviewed several times, and the clerk of court I knew got me Alien's Acceptability to the U.S. Armed Forces. That was somewhere around September 1943. They had a stack of papers on me about five inches thick. I got my draft letter, and it said on the bottom of the letter -- talk about blackmail -- "You can refuse the draft, but you will never be eligible for American citizenship." This still sticks in my craw. The U.S. has been wonderful to me. They could have saved many, many people if they had let them in. You remember the story of the St. Louis? It was the ship full of refugees that couldn't land anywhere. They went all over to Cuba and here and then back to hell.

We lost quite a few family members. My mother and dad finally came over in December 1938 after Kristallnacht. Luckily, I had maintained the papers at the consulate in Stuttgart so that they could come when they were ready. It happened pretty quickly. My dad passed away in 1949 and my mother in 1951.

I was drafted Oct. 17, 1943, and they said I could have another 15 days and I said, "No way, let's go." Strange as it may seem, I was sent to Camp Claiborne near Shreveport. I saw one of the guys I knew from the liquor business and he asked me what I was doing there. He was in personnel, and I told him I didn't want to go to Keesler Field in Biloxi because I had heard how bad it was down there. I wound up [at] Selman Field back home in Monroe, La., in the finance department. We were attached to the Air Force.

Selman Field was a navigation school, and they had a lot of washout pilots. We had 7,000 or 8,000 people on post. I went to Wake Forest to the finance school for 13 weeks.

We came back to Monroe to set up a disbursing office and orders came in for German speakers who wanted to go to Germany. I asked my captain and he said no because we were setting up this office.

Then, it became mandatory. We went up to Greensboro, N.C., and dug foxholes on the golf course. We went overseas in July 1944 on the USS New Amsterdam, and it took us 11 days zigzagging because of the U-boats. We landed at Gourock, Scotland, went to Edinburgh that night and the next day to Warrenton. We then got to where Eisenhower had been and had sheets and pillowcases. The sergeant told us he didn't want to see those sheets and pillowcases when we had inspections.

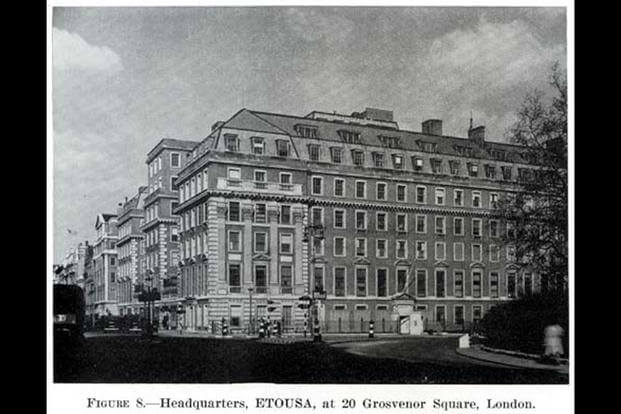

We were transported every morning to 20 Grosvenor Square across from the U.S. embassy. I went into Germany one time with field teams who were capturing German documents and brought them back to England to translate them. During that trip, about a half-mile ahead, one of our teams hit a landmine.

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the U.S. military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Subscribe to Military.com and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.