On July 24, 1944, the Soviet army captured Lublin, Poland, from Nazi Germany as part of an operation to push the Germans back to their border with Poland. On the outskirts of town, Soviet troops encountered the forced labor camp of Majdanek, where Jewish and Polish prisoners, along with captured Soviet soldiers, were slowly worked to death.

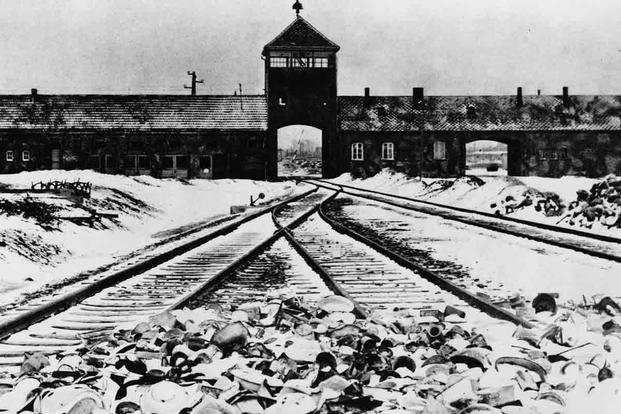

In January 1945, Ukrainian troops from the Soviet Red Army liberated the Auschwitz death camp complex. The Nazis had evacuated most of the 60,000 prisoners held there by then in an attempt to cover up the crime. Seven thousand were still present at its liberation.

When the U.S. Third Army reached the Ohrdruf annex of the Buchenwald Camp, the story of the full extent of the Holocaust began to be revealed to the rest of the world. Photos and documentary evidence from both fronts were soon published in newspapers and newsreels.

It may sound hard to believe today, but the general public and much of the U.S. government didn’t really know what was happening to Europe's Jewish population under Nazi domination. Most knew that they were being taken to camps in Nazi-occupied territories, but few knew what was really going on in the camps.

In April 1944, two prisoners escaped from the death camps at Auschwitz-Birkenau. Seventeen-year-old Fred Wetzler and 25-year-old Rudolph Vrba crawled through Nazi-occupied Poland to reach Slovakia. It was a nearly impossible escape. Once there, they wrote a 32-page report detailing the atrocities committed by the Nazis at Auschwitz.

The report was typed up and distributed by Jewish resistance movements in Slovakia and spread to other countries in Europe. By May 1944, a shortened version of the report was transmitted via Morse code from Slovakia to other Jewish organizations around the world. The hope was that the full truth about what the Nazis were doing with Jewish people would spark more resistance.

News of the genocide broke in Hungary as some 435,000 Hungarian Jews were being prepared for deportation to Auschwitz.

It was also transmitted to the Allied War Refugee Board in neutral Switzerland. The board was the only official body created to rescue Jews from Nazi occupation. When it was transmitted to the Americans, it came with a desperate plea; they wanted the Allies to bomb Auschwitz.

Roswell McClelland, U.S. representative to the War Refugee Board, told the main office in Washington, D.C., that the resistance movements were requesting that the rail lines to the camp, along with the crematoria and gas chambers specifically, be bombed from the air.

John Pehle, the head of the War Refugee Board, sent the request to the Department of War on June 29, 1944. With the Allies fully engaged in the invasion of France, and near-constant Allied bombing raids attacking German war production, the War Department was not open to the idea of special missions.

Meanwhile, the Nazis were ramping up their efforts to liquidate their prisoners. With the Soviet Union advancing from the east and the Western Allies advancing from the west, the Nazis were trying to exterminate the Jews and cover up their crimes. The newly deported Hungarian Jews were being sent to Auschwitz by the thousands every day.

In London, Jewish leaders were trying to persuade the British to bomb Auschwitz as well, belieiving that bombing the camp would save many more lives. Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden supported the idea. Air Minister Archibald Sinclair conferred with the U.S. Army's commander of Strategic Air Forces in Europe, Gen. Carl Spaatz.

With Spaatz, there was no question about the morality of bombing Auschwitz; he wanted to figure out if it was possible for Allied air forces to reach the target. He approached the question as he would any other target. The Allies already had photographs of the death camp, because it was close to IG Farben, a chemical producer.

There was one major problem with bombing the camp: The technology for precision bombing didn't exist. It would take dozens of planes dropping hundred of bombs to hit specific parts of the camp. The bombs that didn't hit the crematoria, the gas chambers or the rail lines might kill any or all of the tens of thousands of prisoners held there.

Eventually, the British decided it was technically impossible. The Americans began to see it as a diversion from the war effort. The Allies did bomb Auschwitz in September 1944, killing 40 prisoners, but the intended target was actually the IG Farben plant, which was making synthetic fuels for the German war effort.

A special air raid to destroy the camp's operations was never carried out, considered by the War Department as being "unfeasible." A far better effort, it was thought, would be to win the war as fast as possible.

-- Blake Stilwell can be reached at blake.stilwell@military.com. He can also be found on Twitter @blakestilwell or on Facebook.

Want to Learn More About Military Life?

Whether you're thinking of joining the military, looking for post-military careers or keeping up with military life and benefits, Military.com has you covered. Subscribe to Military.com to have military news, updates and resources delivered directly to your inbox.