The U.S. military should develop a new emergency weapon: a national roster of individuals with specialized training, experience and clearances, ready to don a uniform at their nation's call.

That's one of the key recommendations to emerge from a multi-year study undertaken by the National Commission on Military, National and Public Service. In a report issued to Congress late last month, the commission called for a "Critical Skills Individual Ready Reserve" of people with few military responsibilities or obligations until the nation called on them in a time of need.

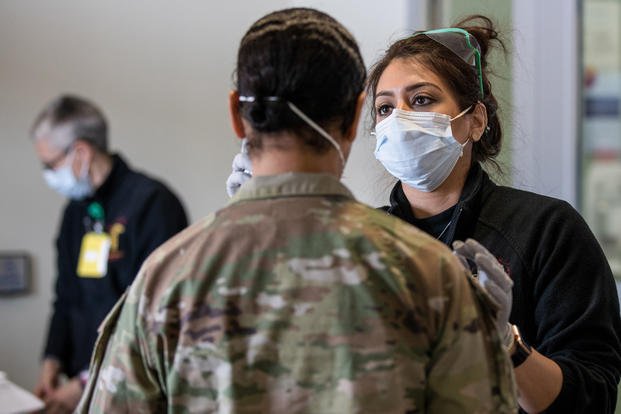

With the report's release amid a global pandemic response that has seen major mobilizations of National Guard and Reserve forces and specialized pleas from the Army for volunteer retired medical professionals to re-don the uniform, the recommendation may have a pressing use case that propels it forward to become law.

The initiative now lies with Congress to move on the report. A planned hearing on the commission's findings was postponed amid the pandemic, and other proposals raised by the commission will likely spur lively debate -- particularly one that would require women to register for the draft for the first time in history. Alongside the report, the commission developed draft legislation that could be used to enact all its recommendations as a single package; that bundle has not been introduced to date.

Related: The Army Asked Retirees in Medical Fields to Come Back. The Response Was Overwhelming

But multiple lawmakers have voiced support for the commission's work and findings, including Sen. Jim Inhofe, R-Oklahoma, and Sen. Jack Reed, D-Rhode Island, chairman and ranking member of the Senate Armed Services Committee, respectively; and Rep. Michael Waltz, R-Florida, a former Green Beret and colonel in the Army National Guard.

"These recommendations can serve as a guidepost as we map out what the future of national service should look like," Reed told reporters in a March 25 conference call.

Waltz told Military.com that he and other members of the For Country Caucus, made up of veteran lawmakers from the post-9/11 wars, are keen to move out on portions of the commission's report.

In February, he and co-sponsor Rep. Chrissy Houlahan, D-Pennsylvania, introduced the National Service GI Bill, which would cover in-state college tuition for AmeriCorps volunteers. He also saw another recommendation become law in late March inside the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security, or CARES Act: the creation of a "Ready Reserve Corps" specifically supporting the U.S. Public Health Service.

"We're seeing municipalities and states try to tap into retired doctors, retired nurses, health care workers," Waltz said.

Regarding the critical skills IRR proposal laid out in the commission report, Waltz said he'd first like to see the military do a better job of cataloguing the skills and capabilities already present within the Guard and Reserve communities.

He encountered the mismatch of military jobs and civilian skill sets among Guard members, he said, while deployed for stability operations in Afghanistan and Africa.

"When we're looking at critical shortages in cyber, stability type operations, if someone understands an electrical grid, I think that's far more useful than being behind a rifle," he said. "I've [also] asked the National Guard if they can tell me how many Guardsmen are working in Silicon Valley."

A Different Kind of Reserve

The proposed critical skills IRR, unlike the traditional Reserve, would not require members to conduct regular drill periods or attend entry-level training.

"Members of such a national roster would be prompted annually to update their personal information and indicate their willingness to remain available for a call-up," states the report, produced by an 11-member panel after more than two years of study. "Unlike members of an IRR, individuals who chose to join the national roster would not be required to muster, providing a more flexible option for those willing to serve when needed."

The concept, the report notes, has its roots in the World War II-era National Roster of Scientific and Specialized Personnel, a tool intended to help U.S. planners assess human resources and capabilities.

The report is intentionally vague about what skills might be sought in such a reserve. In March, the congressionally appointed Cyberspace Solarium Commission proposed a Military Cyber Reserve that would make available to the armed forces a cadre of professionals with hotly demanded cyberwarfare qualifications. Those findings were released just days before the novel coronavirus turned national attention toward a sudden shortage of doctors and nurses.

"We would leave the details up to [DoD] who would be in them in terms of critical skills, what that should look like," Debra Wada, former assistant secretary of the Army for Manpower and Reserve Affairs and one of the 11 commissioners, told Military.com on a March 25 conference call. "But we believe there is an opportunity here to bring in non-prior service who may want to volunteer their service in a time of critical need and to provide those skill sets to the department and the nation for that time."

Wada noted that this IRR would give military officials access to those who already have security clearances and certifications, circumventing a lengthy process in a time of crisis. It would also, in theory, require relatively little overhead in non-crisis periods, allowing planners to build diversity into the roster and plan for a broad range of scenarios.

"As former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates aptly reflected, the United States has 'a perfect record over the last 40 years in predicting where we will use military force next. We've never once gotten it right,'" the commissioners wrote in their report. "In times of emergency, the military may have a pressing need for a skill that was not previously deemed critical."

Also left undictated is the size of the proposed critical skills IRR and how it would be managed and maintained. Another commission recommendation is that the secretary of defense create and maintain a list of the military's current needs regarding personnel with critical skills, both the kind of skills and the number required.

Answering the Nation's Call

All these efforts would work to prevent a return to compulsory service, the commissioners said, drawing instead on the willingness of Americans to answer their nation's call. It's not a hypothetical: On April 2, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio voiced interest in seeking a draft of civilian doctors to be sent to regions, including New York, hit hardest by the virus.

The National Commission considered developing a targeted skills draft modeled after the Health Care Personnel Delivery System -- a standby plan mandated by Congress and supervised by the U.S. Selective Service System that would, if activated, draft doctors in much the way de Blasio requested. But the commission ultimately dispensed with that idea as too complex, noting many skill fields don't have a centralized certification system like the medical field does.

"The Commission believes the best way to preserve fairness and equity and sustain the most lethal and capable military in times of conflict requires enhancing voluntary mechanisms, such as through the creation of a critical skills IRR and a national roster of volunteers," the report found. "Such mechanisms capitalize on the American spirit to rise to the occasion in times of crisis and are consistent with the Commission's conception of the draft as an option of last resort."

Dr. Jacquelyn Schneider, a Hoover Fellow at Stanford's Hoover Institute and a non-resident fellow at the Naval War College, noted that there are many high-skilled professionals who might be motivated to be on standby to serve their country if the model was flexible enough and didn't require excessive administrative work, training or maintenance during inactive periods.

If tasked with creating a critical skills IRR, she said, the military would need to create thoughtful personnel policy, with the right incentives, term lengths and flexibility to make sense for the people on the roster and short enough activation timelines to make them useful in a crisis. Different skill sets may even need different models and frameworks, she said.

But if executed well, she added, this IRR could provide significant value to the military.

"You can imagine if we had a pandemic where we were low on people able to fly," she said. "If you had people in this IRR, you could identify, 'Oh, this person's an airline pilot,' and you could probably spin them up really quickly to fly these airframes."

Waltz said he's optimistic that many of the commission's recommendations will be included in the fiscal 2021 National Defense Authorization Act, the Pentagon's annual budget and policy bill.

"I've seen a number of these commission reports, and they were used legislatively to buy time or delay," he said. "I thought this was a very well done, robust, meaty report. And when it comes with legislative language, that makes it all the better."

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to correct Rep. Michael Waltz's military status.

-- Hope Hodge Seck can be reached at hope.seck@military.com. Follow her on Twitter at @HopeSeck.

Read More: Army Asks 10,000 Recently Separated Soldiers to Come Back for Virus Fight