Army scientists have been working on a canine-like robot that's designed to take commands from soldiers, much like real military working dogs.

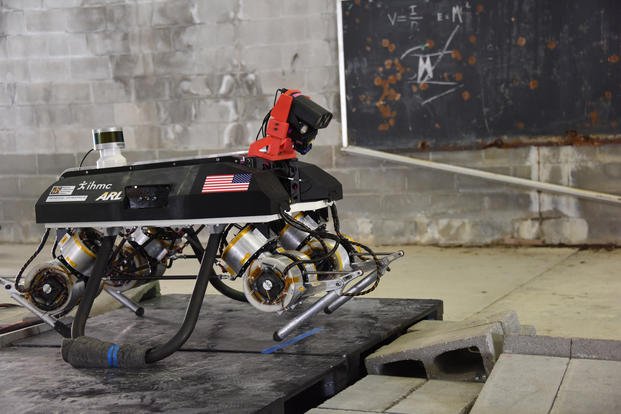

The Legged Locomotion and Movement Adaptation (LLAMA) robot is an Army Research Laboratory effort to design and demonstrate a near-fully autonomous robot capable of going anywhere a soldier can go.

The program is distinctly different from an effort the Marine Corps jointly undertook with the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, or DARPA, in 2010 to develop a four-legged mule robot to take equipment off the backs of Marines in field, officials from the Army Research Laboratory said.

It's much more similar to Marine Corps research efforts around Spot, a four-legged hydraulic prototype designed for infantry teaming.

"We wanted to get something closer to a working dog for the soldier; we wanted it to be able to go into places where a soldier would go, like inside buildings," Jason Pusey, a mechanical engineer at ARL, told Military.com.

"It's supposed to be a soldier's teammate, so we wanted to have a platform, so the soldier could tell the robot to go into the next building and get me the book bag and bring it back to me. That building might be across the battlefield, or it might have complex terrain that it has to cover because we want the robot to do it completely autonomously."

The LLAMA effort began more than two years ago through the Robotics Collaborative Technology Alliance Program, a research effort intended to study concepts for highly intelligent unmanned robots.

"In the beginning we had a lot of wheeled and tracked systems, but we were looking at some unique mobility capabilities ... and toward the end we decided we wanted something that we could incorporate a lot of this intelligence on a [robot] that had increased mobility beyond wheels and tracks," Pusey said.

Army modernization officials have been working to develop autonomous platforms, but one of the major challenges has been teaching them how to negotiate obstacles on complex terrain.

"We picked ... the legged platform, because when we get to an area where the soldier actually has to dismount from the vehicle and continue on through its mission that is the point where the legs become more relevant," Pusey said.

Working with organizations such as NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the Institute for Human & Machine Cognition, ARL has developed a LLAMA prototype that's able to take verbal commands and move independently across terrain to accomplish tasks, Pusey said.

"We wanted it to be very intelligent, so the soldier's head doesn't have to be down and looking at a screen," Pusey said. "Similar to a working dog, we wanted it to be able to go across the way, get into the building, grab the bag and bring it back."

"Right now, when we tell it to go across the rubble pile and to traverse the path, we are not joy-sticking it. It does it by itself."

Program officials have been working to input automatic thinking into the LLAMA. With that capability, it wouldn't have to think about the mechanics of running or avoiding an obstacle in its path any more than a human does.

Digital maps of the terrain the robot will operate on, along with specially identified objects, are stored in internal controllers that guide the dog's thinking, said Geoffrey Slipher, chief of the Autonomous Systems Division.

"You can say, 'go to the third barrel on the left,' and it would know what you mean," Slipher said.

If the map doesn't have objects identified, operators could tell LLAMA to go to a specific map position.

"It would go there and it would use its sensors as it goes a long to map the environment and classify objects as it goes, so then you would have that information later on to refer to," Slipher said.

"As a research platform, we are not looking at it maximizing range and endurance or any of these parameters; the objective of the design of this vehicle was to allow it to perform the functions as a research platform for long enough so we could answer questions, like how this or other autonomous systems would perform in the field."

Pusey tried to relate the effort to trying to teach instinctive human reactions.

"If you slip on a step, what do you do? You normally will flail out your arms and try to grab for railings to save yourself, so you don't damage a limb," he said. "With a robot, we have to teach it that it's slippery; you have to quickly step again or grab something. How do you kind of instill these inherent fundamental ideas into the robot is what we are trying to research."

The LLAMA is also battery-powered, making it much quieter than Marine Corps' Legged Squad Support System, Pusey said.

"One of the problems with the LS3 in the past was it ... had a gas-powered engine, so it was loud and it had a huge thermal signature, which the Marines didn't like," he said, describing how the LLAMA has a very small thermal signature.

Despite the progress, it's still uncertain if the LLAMA, in its current form, will one day work with soldiers since the research effort is scheduled to end in December.

"We are in the mode of this program is ending and what are we going to do next," Pusey said. "There are multiple directions we can go but we haven't quite finalized that plan yet."

Currently, the Army has no requirement for a legged robot like LLAMA, Slipher said.

"One of the objectives of the follow-on research will be to study concepts of operation for these types of vehicles to help the senior leadership understand intuitively how a platform like this might or might not be useful," he said.

-- Matthew Cox can be reached at matthew.cox@military.com.