"We're not going down. We are going to Philly."

That was the message Southwest pilot Tammie Jo Shults sent from the cockpit as Southwest flight 1380 lost altitude in 4,000-foot chunks, having suffered catastrophic damage and an engine loss. The airplane, which had departed from New York's Laguardia airport and was bound for Dallas, would never complete the journey.

Shults became an instant hero when she landed the flight in Philadelphia on April 17, 2018, with 149 souls aboard, averting disaster through quick thinking and careful maneuver. Only one passenger was lost: Jennifer Riordan, who was tragically sucked partially out of a broken airplane window.

Once on the ground, a paramedic marveled at Shults’ controlled heart rate, telling her she had "nerves of steel."

As Shults recalled in her new memoir with the same title, she'd had ample practice in her career as an airline pilot -- and prior to that, as a naval aviator flying fighter jets -- in mastering her emotions and responses to get the job done.

One of the first women to fly the Navy's F/A-18 Hornet in the 1980s, Shults recounts meeting opposition at every turn from male pilots and senior officers who were convinced that she didn't belong. The stories are troubling, from the Navy operations officer who tried to end her career over the fit of her harness to the senior pilot at Southwest who drenched her paperwork in hot coffee after every flight.

But Shults insists on emphasizing the positive. The undesirable instructor duty she was given out of spite for a year in the Navy, she writes, made her confident and ready for anything; the open harassment and disdain from male peers gave her flinty resolve.

"I strive to focus on the heroes and not be distracted by the villains," she writes in "Nerves of Steel."

Related: Navy Releases Service Details for Hero Captain Who Landed Southwest 1380

Shults, 57, spoke with Military.com this week about her book and her experiences. Some answers have been edited for length.

Military.com: You said in your book you have no doubt that women can handle combat. Even decades after you became a Hornet pilot, the debate rages on. Can you expand on what gives you that certainty?

Shults: When I went through POW training -- reconnaissance and survival training through the Air Force program up in Spokane -- seeing how my peers went through that very simulated, but very well simulated, situation, I realized that combat is a frame of mind. There were very physical, very well-prepared young men who struggled and didn't make it through the training. There was an 18-year-old, just out of high school, a girl who she leaned into it and sailed through the program. They picked on her, but ... she ate their lunch and did so well. Combat is a frame of mind that some have and some don't have. And it really isn't attached to gender.

Military.com: You use pseudonyms to discuss multiple aviators who acted atrociously towards you. Are any of them still flying?

Shults: There is one particular one that is still around and in my flight path I've never met him face to face even yet. The others are retired. I've certainly not told those stories before; I was trying to move on, trying to keep going, and sometimes those people were in a position to make that difficult. I looked at how honest to be about those. Struggles aren't limited to just women. Everybody has those, that turbulence in their life. When people read the book, I hope that they realize those things can be the very thing that grooms us, that forges those nerves of steel in us.

Military.com: Were there any particular experiences from naval aviation that came into play when landing flight 1380?

Shults: I have to say that having a faith grounded in Jesus was a big element too. When you think you're going to meet your maker, thinking, 'OK, that question was settled a long time ago -- I'm not going to meet a stranger.' That thought wasn't something that just put me in a panic. Having the Navy training, of course, [helped], especially the out-of-control flight training. I ended up teaching OCF training for a year. I got pulled from the most wonderful stage of instructing into doing what no one wanted to fly, let alone teach, every day. But when you look back, those speed bumps, they were helpful.

Military.com: The Navy just this month marked the final flight of its classic F/A-18 Hornet. What are your memories of flying that aircraft?

Shults: It was a magic machine. When [fellow naval aviator Pam Lyons Carel] and I were sent to the F-18 training squadron there in [Naval Air Station Lemoore, California], they hadn't had women come through there. The shockwave when we arrived was transparent. The F-18 itself was a new level of thrill in flying. It took teaming and organizing details to a whole new level. If I got to pick only one aircraft, it would be the Hornet.

Military.com: I know you had a meeting with Navy officials at the Pentagon after you landed Flight 1380. What transpired there?

Shults: Navy Under Secretary [Thomas] Modly was so kind to invite myself and my husband and our son to lunch at the Pentagon. He had set up a tour and gathered some lady aviators. And so I got to meet some, and some ship drivers, lots of ladies. It was incredible to get to see and to hear, in the women represented at the table, how women were plugged in. Truly I was not there to impart any wisdom -- just there to enjoy the fellowship of other Navy folks. It was a joy to be around people who so loved their country.

Military.com: How do you perceive the environment for female naval aviators has changed since you flew, and what still needs to change?

Shults: [The first female Navy jet pilot, Capt. Rosemary Mariner] passed away earlier this year. An incredible woman of history, and incredible friend of 30 years. There was a "Missing Man Formation" of all women pilots. We got to share the experiences of Rosemary and aviation for women in the Navy -- golden moments. We realized the things that were commonplace when I was in there would never happen now. There still are some that probably have an attitude about [women pilots]. But I don't think it's OK to express it out loud and act on it, as it was then.

Military.com: What's next for you?

Shults: [My husband, Dean Shults, also a Southwest pilot] and I both love our day jobs. Dean and I both got a promotion last week: We're grandparents. We're dedicated to teaching [our grandson] the new names of Pops and Mimi. I volunteer at our local charter school; it's for an orphanage of kids that have been taken out of violent homes. They're absolutely wonderful.

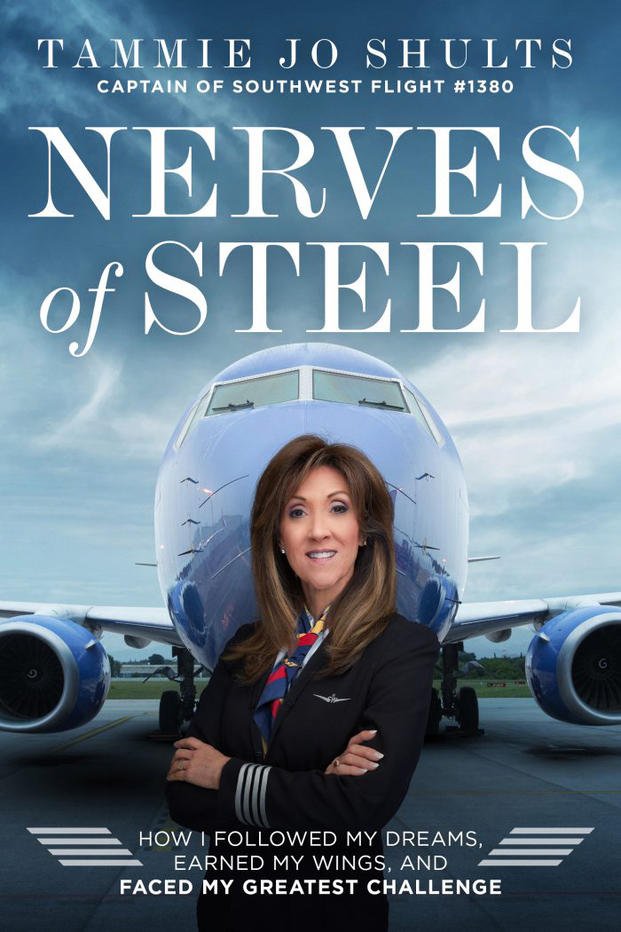

"Nerves of Steel: How I Followed My Dreams, Earned My Wings, and Faced My Greatest Challenge" is now available from W Publishing Group, an imprint of Thomas Nelson.

-- Hope Hodge Seck can be reached at hope.seck@military.com. Follow her on Twitter at @HopeSeck.

Read more: Marines Will Soon Have Better-Fitting Maternity Uniforms and Nursing T-Shirts