On July 4, 1776, the 13 colonies claimed their independence from Great Britain, an event that eventually led to the formation of the United States. Each year on the Fourth of July, also known as Independence Day, U.S. citizens celebrate this historic event.

Which country did we declare our independence from?

The colonies, the populations of which were considered subjects of the King of England, declared their independence from Great Britain. This declaration was formalized with the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, which was drafted primarily by Thomas Jefferson.

What led the colonists to seek independence?

The colonists were a melting pot of not only English, Irish and Scottish but also people from elsewhere in Europe and beyond. In many colonial communities, people spoke their native languages, adhered to the customs of their countries of origin, and practiced their own faiths (although Catholicism was frowned upon if not illegal in the colonies).

But the different groups had one thing in common: "They all had to swear loyalty to the King of England and submit to the law as a British subject," the American Revolution Podcast notes.

Over time, more and more of the colonists began to resent being under the thumb of Great Britain. This tension turned to outrage when the British Parliament imposed the Stamp Act in 1765, putting a tax directly onto the colonists for the first time.

Although the tax was a relatively small amount, the colonists were enraged that they had no say in it. For them, it was a matter of principle. And although the Stamp Act was repealed the following year, in its place Parliament imposed the Declaratory Act, stating that Great Britain had complete power to legislate the colonies.

"The issues of taxation and representation raised by the Stamp Act strained relations with the colonies to the point that, 10 years later, the colonists rose in armed rebellion against the British," according to History.com.

Over the next few years, violent rebellions were common as more and more colonists demanded freedom and viewed the British Parliament as corrupt.

These seeds of rebellion would eventually flower into the creation of the United States of America as a sovereign nation.

"The publication of Thomas Paine's stirring pamphlet Common Sense in early 1776 lit a fire under this previously unthinkable idea. The movement for independence was now in full swing," according to the National Archives.

How the Declaration of Independence was created

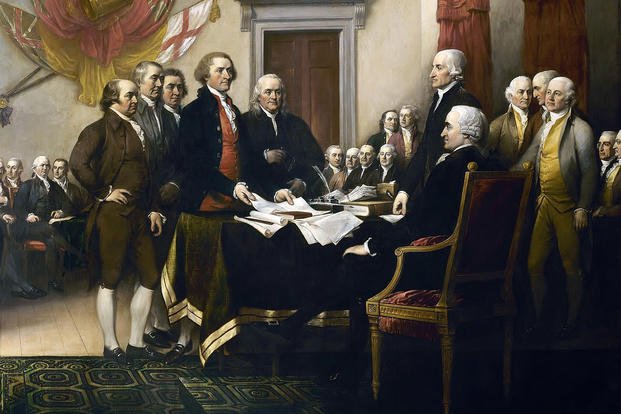

Open conflict between the colonies and England was already a year old when the colonies convened a Continental Congress in Philadelphia in the summer of 1776. During a June 7 session in the Pennsylvania State House (later Independence Hall), Richard Henry Lee of Virginia presented a resolution with the famous words, "Resolved: That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved."

Lee's words were the impetus for the drafting of a formal Declaration of Independence, although the resolution was not followed up on immediately. On June 11, consideration of the resolution was postponed by a vote of seven colonies to five, with New York abstaining. However, a Committee of Five was appointed to draft a statement presenting to the world the colonies' case for independence.

Members of the committee included John Adams of Massachusetts, Roger Sherman of Connecticut, Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Robert R. Livingston of New York and Thomas Jefferson of Virginia. The task of drafting the actual document fell on Jefferson.

On July 1, 1776, the Continental Congress reconvened, and on the following day, the Lee Resolution for independence was adopted by 12 of the 13 colonies, with New York not voting.

What really happened on July 4, 1776?

Discussions of Jefferson's Declaration of Independence resulted in minor changes, but the spirit of the document was unchanged.

One of the main documents that informed Jefferson's wording of the Declaration of Independence was the Virginia Declaration of Rights. The Virginia document also ended up being the basis for the Bill of Rights.

Revisions to the Declaration of Independence continued through July 3 and into the late afternoon of July 4, when it was officially adopted. Of the 13 colonies, nine voted in favor of the Declaration, two -- Pennsylvania and South Carolina -- voted against it. Delaware was undecided, and New York abstained.

John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, signed the Declaration of Independence. It is said that he signed his name "with a great flourish" so England's "King George can read that without spectacles!"

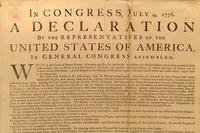

Today, the original copy of the Declaration is housed in the National Archives in Washington, D.C. It's stored under the most modern archival conditions to preserve the delicate, precious document.

The famous preamble to the Declaration of Independence reads: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness."

Why do we celebrate the Fourth of July?

July 4 has been designated a national holiday to commemorate the United States declaring itself to be a free and independent nation.

Although it was actually July 2, 1776, when the Second Continental Congress officially voted to declare independence from Great Britain, it wasn't until July 4 that the finalized Declaration of Independence was approved. It would then be a few more weeks, on Aug. 2, 1776, until most of the delegates were able to travel to Philadelphia to sign the document.

Fourth of July observances "only became commonplace after the War of 1812," according to the Library of Congress. "By the 1870s, the Fourth of July was the most important secular holiday on the calendar."

The U.S. Congress made Independence Day an unpaid federal holiday on June 28, 1870. It wasn't until 1938 that Congress made it a paid federal holiday.

The importance of the holiday lies not only in celebrating the birth of a new, free nation, but in recognizing the significance of the Declaration of Independence, which was -- in the words of Abraham Lincoln -- "a rebuke and a stumbling-block to tyranny and oppression."

4th of July traditions: Fireworks, barbecues and more

The first big 4th of July party took place on the one-year anniversary of independence, in 1777. It was "a spontaneous celebration" in Philadelphia, according to the Library of Congress.

People set off fireworks, built bonfires, lit candles in their windows and lined the avenues with joyful shouts. A band played celebratory tunes. Artillery fire from colorfully decorated vessels on the Delaware River filled the air with booms and gunsmoke.

John Adams described the scene in a letter he wrote the next day, July 5, 1777, to his 11-year-old daughter, Abigail.

"My dear Daughter, Yesterday, being the anniversary of American Independence, was celebrated here with a festivity and ceremony becoming the occasion," he wrote.

Like most big street parties, there was also quite a bit of drinking going on, at least if William Williams' complaints are to be believed. The Founding Father from Connecticut disapproved of the shenanigans and later harrumphed about the "great Expenditure of Liquor" that day, among other transgressions, according to Edmund Cody Burnett in "Letters of members of the Continental Congress."

Celebrations took place in other cities, as well.

Today, fireworks are one of the most common hallmarks of Fourth of July celebrations. And although they date back to the very first July 4th party in America, fireworks were nothing new. They had been used in China for several centuries and were a common facet of royal pageantry in Europe from the Middle Ages.

Related: 10 Unusual Ways to Celebrate the 4th of July

Barbecues are another July 4th tradition for several reasons. For one -- just like setting off fireworks -- cooking meat outdoors over an open flame had already long been associated with celebrations. It's an efficient way to feed a large crowd. And because meat tends to be more expensive than other foods, it's a symbol of prosperity.

Barbecuing is also more common during the summer months, making it a natural for a July Fourth celebration. In addition to meat, mainstays of barbecues in the U.S. include baked beans, coleslaw and corn on the cob.

Related: 4th of July Military Discounts

Interesting 4th of July Facts Every American Should Know

- When the Declaration of Independence was signed, 2.5 million people were living in the newly free nation. That's about the population of Houston now. In 2020, the United States had a population of about 332 million.

- The U.S. motto "E pluribus unum" (Latin for "Out of many, one") was suggested by the Founding Fathers committee on July 4, 1776.

- More than $300 million in fireworks are imported into the U.S. annually.

- Sixty percent of all fireworks injuries occur during the month surrounding July 4.

- Thomas Jefferson designed his own portable writing desk to pen the Declaration of Independence. He used it throughout the rest of his life until giving it to his granddaughter in 1825.

- The two youngest people to sign the Declaration of Independence were Thomas Lynch Jr. and Edward Rutledge, both 26, and both from South Carolina. The oldest was Benjamin Franklin, 70.

- Americans eat 155 million hot dogs on July 4th.

- Three presidents died on July 4th: Declaration signers John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, and James Monroe. Adams and Jefferson actually died on the same day: July 4, 1826. It was the 50th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence.

- For the annual celebration of Independence Day on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., the National Park Service installs 18,000 feet of chain-link fencing, 14,000 feet of bike racks, and nearly 350 portable toilets.

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, Smithsonian Institution, University of Central Florida, Bellevue University, National Park Service, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission

Timeline of events leading to American independence

- June 7, 1776: Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, receives Richard Henry Lee's resolution urging Congress to declare independence.

- June 11, 1776: Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman and Robert R. Livingston were appointed to a committee to draft a declaration of independence.

- June 12-27, 1776: At the request of the committee, Jefferson drafts a declaration that is the basic text of his "original Rough draught." Jefferson's draft is reviewed by the committee before being submitted to Congress.

- June 28, 1776: A fair copy of the committee draft of the Declaration of Independence is read in Congress.

- July 1-4, 1776: Congress debates and revises the Declaration of Independence.

- July 2, 1776: Congress declares independence as the British fleet and army arrive at New York.

- July 4, 1776: Congress adopts the Declaration of Independence, and John Dunlap prints it. These prints are now called "Dunlap Broadsides." Twenty-four copies are known to exist, two of which are in the Library of Congress.

- July 5, 1776: John Hancock, president of the Continental Congress, dispatches the first of Dunlap's broadsides of the Declaration of Independence to the legislatures of New Jersey and Delaware.

- July 6, 1776: The Pennsylvania Evening Post prints the first newspaper rendition of the Declaration of Independence.

- July 8, 1776: The first public reading of the Declaration is in Philadelphia.

- July 9, 1776: Washington orders that the Declaration of Independence be read before the American Army in New York from his personal copy of the "Dunlap Broadside."

- July 19, 1776: Congress orders the Declaration of Independence engrossed (officially inscribed) and signed by members.

- Aug. 2, 1776: Delegates begin to sign an engrossed copy of the Declaration of Independence. A large British reinforcement arrives at New York after being repelled at Charleston, South Carolina.

- Jan. 18, 1777: Congress, now sitting in Baltimore, Maryland, orders that signed copies of the Declaration of Independence printed by Mary Katherine Goddard of Baltimore be sent to the states.

Timeline source: Library of Congress

Want to Know More About the Military?

Be sure to get the latest news about the military, as well as critical info about how to join and all the benefits of service. Become a Military.com member for free and receive customized updates delivered straight to your inbox.