Karina Longworth writes and presents the popular podcast "You Must Remember This," a show that examines the "secret and/or forgotten histories of Hollywood's first century."

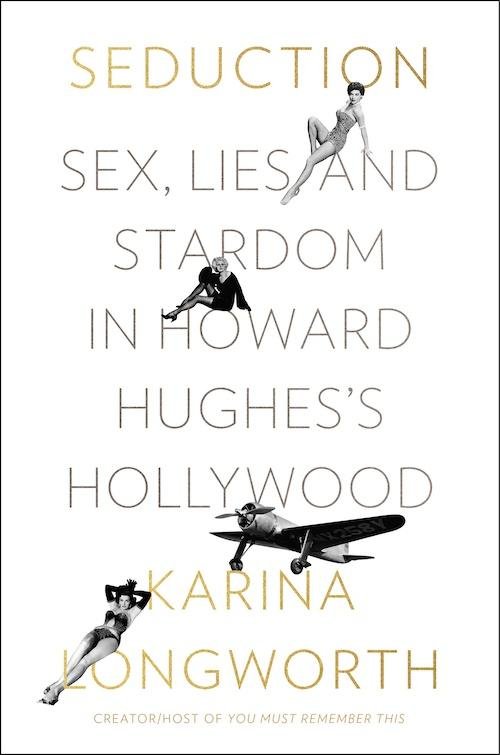

During her research for that program, she developed a fascination with Howard Hughes' role in 20th-century history and used his life as a nexus for a book about the history of women in the motion picture business.. "Seduction: Sex, Lies and Stardom in Howard Hughes's Hollywood" is the outstanding result and the book is out now.

Longworth tells the stories of women who either had personal relationships with Hughes or had professional connections. Some had both. For long stretches of the book, Hughes himself recedes into the background but he's always there as the connective tissue between these women's stories.

Most of the names will be familiar to anyone who watches Turner Classic Movies: Ava Gardner, Katherine Hepburn, Bette Davis, Lana Turner, Jean Harlow, Jane Russell, Ida Lupino, Billie Dove, Faith Domergue, Jean Peters and Terry Moore all play prominent roles in Longworth's tale. The first half of that list features some of the biggest stars in Hollywood history but the second half features a few actors who are beloved by serious fans and scholars of old movies.

Longworth explores just why Howard was so screwed up but doesn't let him off the hook. His behavior towards women was indefensible, even as he gave a few of them valuable career support that helped make them famous. Of course, he also acted abominably towards his business partners in the tool, movie and aircraft businesses as well and the American press celebrated his behavior and success.

If that sounds familiar to anyone who's been following the #metoo moments of the past year or so, that's about right. Howard's more toxic behavior has inspired generations of businessmen and he would've taken quite a hit for his actions if he was around today.

The bad parts of Howard Hughes frequently collide with the drive and genius that made him a business pioneer. Longworth gives credit for the accomplishments while taking a long, hard look at the complicated relationships he had with women.

We've got an excerpt from the book that focuses on his notorious test flight and crash of the experimental XF-11 plane in July 1946. He walked away and recovered from his physical injuries, but his already eccentric behavior just got weirder and more reckless over the last three decades of his life.

Check out the beginning of "Chapter 17: An American Hero" below.

The Fourth of July fell on a Thursday, but the party stretched through the weekend. On July 5, 1946, guests began to arrive at the house of Bill Cagney (brother of James), on the shore at Newport Beach. Jean Peters, a brand-new Fox contract girl, showed up on Friday with most of the rest of the party, and on Saturday, Howard Hughes joined them. That night, according to Modern Screen magazine, Jean Peters "fell in love for the first time in her life."

Hughes and Jean Peters did meet for the first time that weekend at Cagney's house, though whatever emotion Jean felt at first sight for Howard was likely overshadowed by the chaos that shortly followed. That Saturday night, Hughes, Peters, and a few other guests flew to Catalina for a satellite party. And then, Peters recalled, "Sunday he came back to his airport in Culver City to test the plane in which he crashed."

On July 7, 1946, Howard Hughes manned the controls for the inaugural test flight of the XF-11, a prototype reconnaissance plane that Hughes had designed for the U.S. government during wartime as part of a massive defense contract Hughes had been awarded in 1943. Hughes hadn't been able to deliver a single plane before the end of the war, after which the Defense Department had scaled back their order, from 101 planes to the two that were in the process of being built. As his test flight would prove, over a year after D-Day, the XF-11 still wasn't ready.

After lifting off from the Culver City airstrip and smoothly cruising at 400 mph over the Pacific Ocean, Hughes turned the plane around to return to Culver City, victorious—just as he had been during the speed trial that ended in the crash landing in the beet field, just as he had felt when first flying the Sikorsky. And, here, just like those other times, before he could get the plane safely on the ground, something went wrong. Though the instrument panel showed no malfunction, the aircraft began to drag to one side, as if a massive weight were pressing down on the right wing. Hughes couldn't figure out how to fix it in midair. He went looking for a place to make an emergency landing. A lifelong golf aficionado, he easily spotted the green rectangle of the Los Angeles Country Club golf course, just east of UCLA. Hughes steered the malfunctioning craft there, but there was not enough time.

The plane hurtled into a residential street in Beverly Hills, tearing half the roof off the home of a dentist. The bad right wing slashed through the upstairs bedroom of the dentist's next-door neighbor. Hughes's plane bounced off a third home's garage, took out a row of poplar trees, and finally crashed once and for all into the home of Lieutenant Colonel Charles E. Meyer, where it burst into flames.

Two other military men, Marine Sergeant William Lloyd Durkin and Captain James Guston, who happened to be in the area, dragged Hughes's unconscious body out of the wreckage. At the Beverly Hills Emergency Hospital, doctors examining his injuries weren't optimistic Hughes would live through the night.

In the days and weeks immediately following his hospitalization, whether or not Howard Hughes lived or died became a subject of national obsession. The Los Angeles Times referred to Hughes as "the 40 year-old, slightly deaf, handsome bachelor whose fortune has been estimated at $125,000,000." The top half of their page one was taken up with a photo of the wreckage, the downed plane surrounded by the rubble of the neighborhood it took out. Depending on the publication, Hughes himself was deemed either to be "near death" or given a "fighting chance of survival." He was said by some to be suffering from shock, and yet his brain was apparently working overtime. While in critical condition, and against doctor's orders, he called his secretary in and dictated tasks to her until the doctors made her leave the room.

Three days later, on July 11, Hughes's personal doctor, Verne R. Mason, briefed reporters. "Howard Hughes has suffered a turn for the worse in his fight for life," Mason announced. Hughes's left lung's inability to function was requiring full intubation, and yet, in what was described as an "amazing revelation," from his sickbed Hughes croaked out a message that he asked to be passed along to the army: "Find the rear half of the right propeller and find out what went wrong with it—I don't want this to happen to somebody else."

Every day there were new headlines about Hughes's condition—about how he had beaten the odds, about how he had woken from a coma with the design in his head for a new and improved hospital bed, which he then gave orders for one of his factories to produce. When grasping for dramatic details about the crash itself or Hughes's subsequent condition, and coming up short, the papers put their reporters on the case of recounting the famous feminine faces seen in the hospital waiting room. Jane Russell was there, as was Lana Turner, to whom there were currently rumors that Hughes was engaged. Neither Russell nor Turner was admitted to see Hughes, with Lana reportedly waiting until dawn to no avail, "greatly upset and weeping."

Ultimately Hughes made a spectacular and miraculous recovery, but if his body bounced back better than anyone could have imagined, in some ways he was changed permanently by the crash. He was left with a scarred upper lip, the beginnings of a dependence on opiates that would eventually become paralyzing, and a seemingly skewed sense of his own mortality. A number of his actions over the remaining thirty years of his life—from the defiant congressional testimony he'd deliver a year later defending the work he had done for the Defense Department to his strip-mining of RKO Pictures under the cover of anti-Communism, to his increasingly compulsive collection of starlets, whom he'd stash away in apartments patrolled by bodyguards and spies, to his circa-1960s attempt to buy up nearly every casino in Las Vegas—would strike many observers as evidence of madness.

There may have been something else going on, too. Howard Hughes was a man whose early years were full of death: his mother died when he was sixteen and his father dropped dead two years later; four men died during the making of his directorial debut, "Hell's Angels"—and this was all by Howard's early thirties. He had now been involved in a number of plane crashes and accidents that killed others and all of which could have killed him. No wonder he emerged from the hospital and went on to act—first in his fearlessness and then in his recklessness, and finally with his total disregard for the sanctity of his own body—like a man who didn't believe he could be killed.

He could be, of course. In thirty years, he'd be dead. But in a dozen years, he'd be married.

From SEDUCTION by Karina Longworth, published by Custom House. Copyright © 2018 by Karina Longworth. Reprinted courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers. https://www.harpercollins.com/9780062440518/seduction/