"First Man" tells the story of astronaut Neil Armstrong, the first man to walk on the moon. Now in theaters, the movie gives Ryan Gosling one of his best roles as Armstrong and firmly establishes director Damien Chazelle ("Whiplash" and an Oscar winner for "La La Land") as one of the most gifted and versatile filmmakers working today.

Apollo 15 astronaut, West Point grad and Air Force veteran Al Worden is one of an exclusive group of men who flew to the moon and he became friends with Neil Armstrong after both men completed their NASA service. He took some time to give us some background on his own career, the space program and offer an endorsement for "First Man."

The movie aims to capture how fast and reckless NASA had to be to win the space race with the Soviet Union. Astronauts piloted ships loaded with untested technology and a few died in the service of our nation's goal.

In addition to Gosling's outstanding work, "First Man" features great performances from Corey Stoll (Buzz Aldrin), Jason Clarke (Ed White), Shea Whigham (Gus Grissom), Pablo Schreiber (Jim Lovell), Kyle Chandler (Deke Slayton), Ethan Embry (Pete Conrad), Lukas Haas (Mike Collins), Christopher Abbott (Dave Scott) and, especially, Patrick Fugit (Elliott See). Claire Foy gives an outstanding performance as Neil Armstrong's wife Janet, a part that couldn't be more different than her upcoming turn as Lisbeth Salander in "The Girl in the Spider's Web."

Al Worden believes in space exploration, possibly now more than ever. Read our conversation for a perspective that should be heard in Washington.

Can you tell us about your military career before you joined the space program?

I went to West Point back in the 50's. I graduated high school in 1950 and went to the University of Michigan for a year, but I knew I couldn't sustain that because my family had no money to send me to college and I had a one-year scholarship.

I realized that I needed help getting through college. My dad went to our local congressman and I took a civil service competitive exam throughout the State of Michigan. I got an appointment to West Point out of that.

I graduated 1955 and went into the Air Force because I thought it was the more technically advanced service at that point. In 1955, one-third of the students from West Point and one third from Annapolis went into the Air Force to make all three services equal. The Air Force Academy graduated its first class in 1958.

So I went in the Air Force. I had only flown an airplane one time, so I wasn't sure about that. I got down to McAllen, Texas, where I went through flight training. I started flying T-34's and then T-28's and realized that there was an aspect of flying that I was very attuned to, and that was instrument flying. I could fly the heck out of an airplane under the hood. That was really my best thing.

I went to Laredo to get jet qualified in T-33's. From there, I went to Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida to get transitioned into the F-86D all-weather fighters. I spent the next six years flying in an all-weather fighter squadron and that was great with me because, as I said, instrument flying was really my thing.

I realized that some things were happening and that Air Defense Command was going to ask me to transfer out to Colorado Springs and take a desk job. I decided that if I was going to take a desk job, it had to work both ways.

I got in my car and drove across the Potomac to the Pentagon, where I got hold of an old master sergeant who was head of the Civilian Institute Program for the Air Force. I talked to him and we finally agreed that he would give me orders going back to college instead of going to Air Defense Command Headquarters.

I went back to the University of Michigan for two-and-a-half years. While I was there, I became the Ops Officer for all the Air Force pilots who were there. I was studying and going to the college during the week. On weekends, I was at Selfridge Air Force Base north of Detroit, where I was doing a lot of flying, keeping everybody current, giving the instrument checks, that kind of thing.

I was told by some senior officers that I should apply for test pilot school, which I did. I did not get on the list for Edwards, but I was selected to go to England.I spent about a year-and-a-half in England flying with the RAF and going through the Empire Test Pilot School.

Just before we graduated, Chuck Yeager came over with the test pilot school from Edwards. They came right over to me and asked me to come back and teach at the test pilot school in Edwards.

I had already been assigned to Bedford Flight Research Center in England for another two years. I thought that was gonna be a problem, but it turned out not to be. The British were very happy for me to go back and become an instructor. So I did that and I was there February of '65 until April of '66, about a year and a half.

I think it was December of '65 when NASA opened up a request for applicants. Then I figured I had nothing to lose. I had, at that point, three master's degrees, I was a certified test pilot, and I was actually an instructor in a test pilot school. So I felt I had nothing to lose, so I threw my name in and eventually got selected into NASA.

What group of astronauts was that?

We were the fifth group of astronauts selected by NASA. There were 19 of us who went into the program. We were picked specifically for the Apollo Program, as far as I know. That's because most of us had a pretty good academic program, plus good flying. And if we didn't have a lot of flying, we were test pilots. So it was a combination of all that.

In the earliest days, NASA's criteria was all about how well you flew.I guess as time passed, they were looking for people who had multiple skills to join the program.

When the program first got started with the Mercury Seven, they were looking for guys just to fly the spacecraft. As time went on, they got guys in the Gemini Program, the Tom Staffords and the Frank Bormans and the Jim Lovells of that era, where they would become commanders and they would fly in the Gemini Program to develop and certify all of the different things we would have to do to make lunar landings, such as long duration flight. I think Frank Borman and Jim Lovell hold that record of 14 days. Rendezvous and docking, which was done a couple of times, and doing spacewalks.I think Gene Cernan, Dick Gordon, and probably Buzz Aldrin all did spacewalks under Gemini flights.

The developed the procedures to do all those things, opening the way for the Apollo Program.

I think my group was actually probably a little bit more academically advanced than the groups before. But whatever it was, we got picked for the Apollo Program. I would say over half the guys in my group ended up making flights. Let's see, Apollo 13 was Fred Haise and Jack Swigert. 14, Stuart Roosa and Ed Mitchell. My flight, myself with Jim Irwin. 16 was Charlie Duke and Ken Mattingly. And 17 was Ron Evans. All of those guys were in that fifth group.

When did you meet Neil Armstrong?

I knew Neil from the program, of course, when I got there, but I never really was around him very much. He was very busy doing things, getting ready doing his Gemini flights. I got there towards the end of the Gemini Program, so he had already made his Gemini flight when I arrived. I saw him once in a while in the office, but we weren't close then.

I got to know Neil a lot better later on. After I had retired, he retired, I was Chairman of the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation and I had quite a few meetings with Neil and lots of letters and emails and texts back and forth and all that kind of thing. We became pretty good friends. He was a great guy, very friendly. Have you seen the movie?

Yes. I was knocked out by it. One thing that I thought they did incredibly well was convey the improvisation and the danger in the space program, showing how much further they were trying to go than the technology should have allowed.

The movie is really a story about Neil Armstrong. It's not really a story about spaceflight. That's a small part of the movie, in my mind. The movie is really about what drove Neil, how he approached problems, how he approached good things and bad things and what kind of a person he was.

There are space scenes in the movie, but they're not the principal part of the movie, as opposed to other movies that you've seen, like "Apollo 13." I think "First Man" is exactly what the name implies. It's all about the first guy to walk on the moon and what kind of a person he was. It's more of a personal movie, more of a personal story, than it is a space story.

In the action scenes that are in the movie, I think "First Man" conveys more of the sense of how dangerous it was, than maybe a movie like "Apollo 13" did.

Exactly. It starts right off with X-15, then the Gemini, then the LLTV, and then Apollo. I think Damien Chazelle really gives the audience a visceral feel for what it was like to fly in those different machines. I think that's a real, real big point for the movie is that he's done that better than anybody's ever done it.

Even the opening scenes where he's flying the X-15, it is incredible. He shot all that from inside the cockpit looking out. And it's absolutely amazing and certainly gives you a feel for what it was really like.

Now, in some of the scenes I would probably say that the real-life shaking, rattling, and rolling and noise was probably not quite what they show in the movie, but I think they were doing that for effect too.

Tell our readers about your own Apollo mission.

We were the backup group for Apollo 12. We trained for a year-and-a-half to fly the machinery, to get out there and get back and do what we had to do. And then after Apollo 12 flew, we were named as a prime crew on 15. For the next year-and-a-half, we pretty much focused on the science we were going to do once we got there.

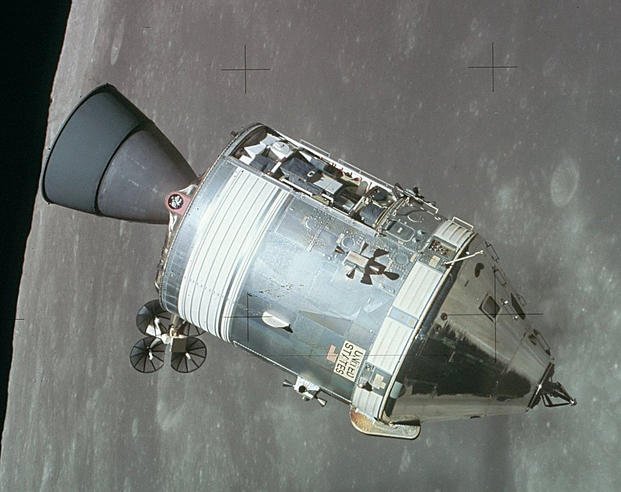

We were a little different from what had been done before. For example, we carried the first lunar rover. But I think even more importantly, we carried a scientific instrument module in the service bay into lunar orbit. It had two cameras, a high-resolution and a mapping camera. They had a whole suite of remote sensing devices, up to and including a mass spectrometer. We carried a little sub-satellite.

We were really focused on the science that we needed to do on our flight and I think we were very successful at that. We accomplished everything that we were supposed to do, but we really focused on the science once we got there. After three years of training, flying was a piece of cake, really.

Had the technology of the capsules and the landers and the rockets evolved since Apollo 11?

Yeah. We were the first of what they called the Block IIs, Apollo spacecraft, the command module. There were some changes, they weren't drastic, they weren't big. As an example, in our spacecraft for the first time, they had to put a whole panel in the cockpit that controlled the scientific instrument module in the service bay.

So we had all that additional stuff that we had to be concerned about, but I think the basic structure for guidance, navigation, radios, that kind of stuff was the same. There were probably some little fixes here and there for stuff that might not have been quite right before.

We had very little trouble on our flight. We only had a couple of incidents where there was any question at all about a system, and they were pretty easy to solve. So we really had no problems going out and coming back.

It's hard to believe it's been almost 50 years since the moon landing. You are part of a very tiny group of individuals who have had the experience of space exploration. Is that something that bonded all of you together as time passed?

Well, it didn't bond us when we were in the program because everybody was jockeying for position. But yes, as time has gone by, it's this sort of fraternity, all of the little petty squabbles and arguments and that kind of thing have gone away. We get along pretty well today.

It's kind of nice to see the guys. 24 of us went, I think there are 17 of us left. The number is not going to get bigger. I cherish the times that I get to see the guys. In the astronaut office in Houston, I had Paul Weitz and Jim Irwin as my officemates and they're both gone. So it's pretty close to home.

As a nation, we've lost our commitment to space exploration. Do you see advantages to restarting and re-committing to the space program?

The leaders in this country completely misunderstood the value of the space program to this country. If you go a long way back, let's say to the late '50's, DARPA and NASA were instrumental in the design of what we call silicon chips. And silicon chips made solid state devices which are much lighter and robust than the old vacuum tube stuff, which the Russians were still using at the time. One of the things that made our flights so successful is that we had that really good technology.

Titanium was another one. We developed ways of working with titanium that people thought couldn't be done. You couldn't weld titanium. Well, they found out a way to do that.

All of that technology, which filtered down through DARPA to the military to NASA to commercial manufacturers made possible all of the electronic stuff and material stuff that have made this country so successful over the last 30 years. It mostly came out of the space program because NASA was the funnel from classified programs through NASA to commercial manufacturing. We wouldn't have any of these big flat panels or we wouldn't be talking on the cell phone like this today if it hadn't been for that.

That's what made this country so successful. Most leaders in this country have failed to see the value of the technology that NASA developed. That's why space exploration on its own was not important to the presidents who have served since, and so the program got knocked down.

We're getting one-tenth of the appropriations today that NASA got back in 1969. We need to make the point that the future uses of technology that we develop to get somewhere is what's important about the space program.

The space program is not as robust as it used to be. When NASA funding started dropping, NASA changed from a goal-oriented organization to a bureaucratic organization where saving your job was more important than what you did.

They are very safety-conscious today. They are so conservative that we're almost not getting anywhere. I think the Orion is just a carbon copy of Apollo, but a little bit bigger. The SOS is another Saturn V with some solid boosters strapped to it. It's kind of regenerating old technology and a lot of that is because of the bureaucracy that we see today.

People are averse to having something bad happen on their watch. Space is a risky business. There are going to be problems, there are going to be accidents. We have to face up to that and fix the problems as we go. That's what's eventually going to get us where we need to go.

NASA was the tip of the spear during the Cold War. We were trying to win a war. Obviously, any war you fight has casualties.

That's probably true. John F. Kennedy very clearly made the Lunar Landing a priority to beat the Russians. There's no question about that. The unintended consequences of that was the technology that was developed. I don't think anybody has ever really picked up on the importance of that. At least, I've never heard anything, anyway.

Those of us who were coming of age during the space program were also growing up at a time when the country was probably even more divided than it seems now. For me, space exploration was a way for young people to understand what the collective could accomplish when it worked together.

We need that mentality today, but we don't have it. There's too much divisiveness in the people in Washington. Everybody is fighting everybody else these days. Some of this other stuff is going by the wayside, I'm afraid.