When Kristie Crow married her husband, a soldier in the Army, she had no idea how her husband's career would impact hers.

Knowing that military spouses face stubbornly high unemployment rates, often around 20%, Crow decided to pursue a master's degree in clinical social work in order to be more marketable as she moved from state to state.

Crow thought she could meet license requirements in the three years her husband would be stationed in Washington state, but his orders were cut short, leaving her shy of the clinical hours needed to obtain her license. Off to Virginia they went, but their 22-month orders were two months shy of that state's 24-month license requirement.

When they later moved to Hawaii with three-year orders in hand, Crow finally had enough time to obtain her Licensed Clinical Social Worker certification, or LCSW, and log the hours required to be eligible to transfer it to her current state of residence, Virginia.

Now, despite having eight years of clinical experience, Crow has been licensed for only a little over a year, and she is worried about how her husband's next set of orders will impact her career.

"There are definitely states where it's like, 'Oh, I hope we don't end up there,'" said Crow.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates that 34% of military spouses work in fields that require occupational licenses. And without the ability to transfer licenses across states, those spouses aren't able to take advantage of the hard work they've already put in to advance their careers.

For more than a decade, the Pentagon has been trying to help -- with limited success.

But tucked not so secretly inside the unassuming 'Veterans Auto and Education Improvement Act of 2022'' is an update to the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act (SCRA) that allows military spouses and service members to transfer any "covered" professional license, except one to practice law, across state lines. The law is meant to supersede the complex negotiation process currently underway between the states and Defense Department.

But it's not clear how states are going to respond to the new law.

"My concern is that this actually puts military spouses at risk without proper guidance for how it's going to be implemented or accepted by states," said Michelle Turner, vice president of clinical talent and delivery for Hazel Health, a company that provides school-based telehealth services across 14 states. Turner is responsible for the recruiting and hiring of clinical providers, including pediatricians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants and licensed therapists. She is also a military spouse herself.

Crow works for Hazel Health. Turner got the company's lawyers to sort out directions for how Crow could apply to transfer her Hawaii license to Virginia, using the new law.

"I applied on Monday, and I had my license emailed to me on Saturday," said Crow, after applying for her Virginia license citing this new law. Although Virginia and Hawaii have similar license requirements, making the approval process more straightforward, Crow was astonished at the speed with which Virginia processed her request and is cautiously optimistic.

But there's no guarantee that every state would work so expeditiously. In Crow's career field, each state has different licensure requirements.

And any delays in getting a new state to accept a license can have a direct impact on spouses' wallets.

"My company paid me less because I wasn't LCSW, and I was having to work under someone else's full license," said Crow, "which just adds to the military spouse gap in wages that we sometimes experience because of all of our frequent moves."

For some types of work requiring licenses, moving to a new state is straightforward. A military spouse cosmetologist covered under an existing compact or the revised SCRA should be able to apply for a job with their out-of-state license and hit the ground running.

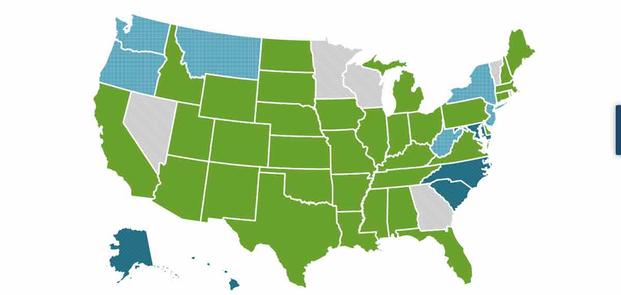

The Nurse Licensure Compact, for example, allows a military spouse with a valid nursing license in one state to transfer their license to a participating state without having to be recertified. However, six states don't participate in any of the nine existing compacts, including California, the state with the highest number of active-duty military residents.

Spouses in the medical field must also hold a valid license in the new state to obtain malpractice insurance or sign up to become a Medicaid provider, both of which are required by employers. Some states require additional training to ensure providers don't inadvertently violate state law.

"In North Dakota, where abortion is illegal, I may someday be required to report the intent to seek an abortion, but I am not required to do so in California," said Crystal Bettenhausen-Bubulka, LCSW, MSG and Navy spouse who is licensed in California, Hawaii and North Dakota -- a process that took her six years and cost roughly $4,000. "It is very unethical to just give a social worker a license without making sure they understand the state laws."

How these state-level requirements will change under this law is unclear.

The Pentagon is also trying to sort out how the law will impact military families.

"The department is still in the process of determining what information will be most helpful to military families concerning the newly enacted federal provisions under the SCRA and how issues might best be addressed," said DoD spokesperson Lisa Lawrence.

The DoD, however, is not without leverage. In 2018, the then secretaries of the Army, Navy and Air Force wrote a memo to the National Governors Association, stating "we will encourage leadership to consider the quality of schools near bases and whether reciprocity of professional licenses is available for military families when evaluating future basing or mission alternatives."

The Defense Department spent nearly two decades working on the issue before congressional action.

In 2004, the undersecretary for defense for personnel and readiness formed the Defense State Liaison Office (DSLO) to correct issues arising for military families as they move and work across state lines. Since its inception, the DSLO portfolio has included family law, education, occupational licensure and employment support, consumer protection, voting, health policy, National Guard support and state judicial systems.

By all accounts, the DSLO is highly successful, having negotiated more than 1,000 state bills, and worked with families, states, professional licensure boards and legislators to help alleviate the barriers presented by the military lifestyle. The office regularly posts state-level legislative wins on Military OneSource for military families to track.

"The goal of this was to replace all of those [DSLO efforts]," said Rep. Mike Garcia, R-Calif., a Navy veteran who originally introduced the Military Spouse Licensing Relief Act of 2021 that later became part of the January law.

"Since I've been in office, almost three years, everyone keeps telling me that the states are working on this," Garcia said. "First of all, not all states are working on reciprocity laws; some are and some aren't. Second, they're moving very slowly in that process. And third, it's not uniform."

According to Garcia, Congress intended this legislation to be a "forcing function to get the states to conform to one requirement, to one regulation and one threshold."

"It's very clear," he said. "You've got to honor the professional license from one state to the next."

How simple the process of transporting licenses will be is still being ironed out, and for now the Pentagon is largely deferring to the states.

"The states, and not DoD, must determine how existing state licensure portability policies align with the newly enacted federal law," Lawrence said. "The department looks forward to working with states to support their efforts to implement the requirements of the federal law."

If a military spouse is unsure of how this new law affects them, they can contact their licensure board or congressional representatives. If state is found in violation of the SCRA, service members, military spouses and families are encouraged to file a complaint with the Department of Justice (DOJ).

States with licensure reciprocity policies are marked green (DSLO via Military OneSource)