FORT MEADE, Md. — War is a miserable business; when a Soldier isn't engaged in active combat, he's often bored. During World War II, Soldiers endured harsh weather, uncomfortable quarters and unsatisfying combat rations, but nothing could cure their ills faster than hot chow and mail, said Dr. Michael Lynch, research historian with the U.S. Army Heritage and Education Center, or USAHEC.

"I think the cook traditionally in the Army has always had a sort of bad rap," Lynch explained, "Unfairly, because it's always assumed the food is bad. Sometimes, it was at that time, and it's always assumed it's the cook's fault. But, when the cook was able to provide hot food, then he became a hero."

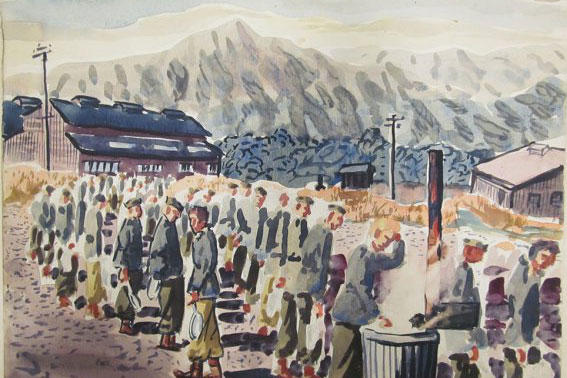

The USAHEC opened the "Cook, Pot and Palette" exhibit, July 15, to highlight the contributions of one Army cook, Sgt. Angelo Gepponi, a 77th Infantry Division Soldier during World War II.

Gepponi, the son of Italian immigrants, dropped out of school and began working in a restaurant when he was in the 8th grade, said James McNally, curator with the USAHEC.

He attended the National Academy of Design for a time, working as a janitor at the school in the evening. When the war started, Gepponi was drafted into the Army at the age of 31, where he was assigned a position as a cook.

All of the pieces in the exhibit were created by Gepponi while he was on active duty, and include examples of watercolors, pen and ink works, and portraits of his fellow Soldiers and the places they served, McNally said.

Gepponi was stationed in the Pacific theater with the 77th, which made it a little more difficult to get his kitchen set up, Lynch explained, because the islands they would occupy had to be captured first. Soldiers would eat K-rations while in combat zones or while waiting for the kitchen to be brought in for hot food.

"There was a unit for breakfast, lunch and dinner," Lynch said of the K-rations. "Typically, they would have some sort of meat, some sort of bread or cracker, and the same sorts of things that we would have today, such as coffee, powdered hot chocolate, that kind of thing. ... What's interesting about K-rations is they had cigarettes, which we don't include today."

They would also have water purification tablets, and gum or candy, Lynch said. "That was usually a standard to make the rest of it palatable."

Part of daily life in a combat zone — in addition to waiting for hot chow — was improving the position the unit was in, Lynch said. Soldiers would not only improve their fortifications, but also their comfort, such as putting wooden boards under their tents. Replacement Soldiers would be trained and brought in; weapons and gear would be cleaned; Soldiers too long on the front lines would be sent to the rear for rest and relaxation.

Gepponi would depict these aspects of life in his art, providing a window into behind-the-scenes life as a Soldier. He would often send sketches home through V-mail, a mail system that had Soldiers write their letters on a form that was photographed and converted to microfiche for transport.

"He drew on that page with black and white ink," McNally explained. "He would do a drawing of where they were, it could be setting up camp, it could be a card game, it could be men heading to the showers, it could be on patrol, whatever was happening at the time when he sat down to write a letter home. He'd do a V-mail with just a picture and then send that home." The exhibit at USAHEC houses about 18 of Gepponi's V-mail sketches.

Gepponi served with the Army for three years, and was honorably discharged, Dec. 15, 1945, just before the occupation of Japan, McNally said.

"Upon release from the Army, he immediately signs up to study art and teacher's education at NYU [New York University] in New York," he said. Gepponi was assigned a teaching position at Cliffside Park High School in New Jersey after graduation.

As a civilian, Gepponi taught, painted and traveled until he retired in 1976. He continued to paint throughout his retirement and "thanked America for the great opportunity to serve his new country, and also become the artist that he always dreamed," McNally said.

Gepponi's prolific career as an artist led to him being represented in both private and public collections around the world, McNally continued. But perhaps his most significant contribution to art and to history is his mentorship of young artists, to include his own nephew, Dennis Baccheschi.

"Angelo lived in New Jersey when I was growing up," Baccheschi said. "I started to get to know him on his visits, maybe from [the] age of 5, and I was always fascinated with his visits because ... he spoke like no other person I ever heard, always rationalized about everything.

"He did artwork while he was here, which I think was the beginning of my inspiration. Every time he left I would start drawing pictures and I was pretty good at it. I think I somehow got some of Angelo's genes along the way," Baccheschi said.

When Baccheschi started taking art classes in high school, his uncle would encourage and critique him during their visits. Gepponi encouraged his nephew to go to an art college, as well.

"After art school I got drafted, and ironically I went to Vietnam," Baccheschi said. "I was driving a fuel tanker for three months, but I was doing artwork of Soldiers and scenery on the side, and finally a captain asked me to do something [an art piece] for him, and then a general saw that and cut orders for me to become an engineer artist."

Baccheschi ended up in headquarters, which turned his tour of duty from something hazardous into something "rather pleasant." He had several pieces published in Army magazines and newspapers, his work focusing on landscapes and different engineer operations, such as building culverts and bridges, and even a mine sweep. "I rode in a Jeep at the tail end of a mine sweep taking photographs and when I got back I did a painting of that," he said.

Baccheschi served in the Army for 19 months, 15 of them in Vietnam, before separating as a specialist 4th class. He continued his art career after his separation, to include opening and operating a gallery for five years.

"I take [art] for granted these days. I think probably the original inspiration is from Angelo. I learned to appreciate aesthetics and to this day I still photograph landscapes all over," Baccheschi said. "I just like the peacefulness. Unfortunately, I do live in the city, but I travel a lot and stay in state parks and national parks; if I can't paint on location, I will work [from] my photos."

Baccheschi believes that his uncle's greatest contribution to the art world is inspiring and educating others. He wrote about his uncle in a letter to USAHEC: "[Angelo] worked very hard with his students as he tried to help and inspire as many as he could. Angelo once said 'I do this not because I have to, I do it because I love to.'" One of Gepponi's students, Frank Fezzo, went on to become a combat artist in Vietnam.

Gepponi's unique work gives viewers a "very real Soldier's perspective," Lynch said. "It's such a personal connection that's hard to get from an official photograph," he added.

McNally said that having visual representations of history is important because it is universally relatable and understandable. "It's a witness to history, and it's a witness through one man's eyes so we get his story, and we find out a little bit more about things. You find out what happened, you found out how things were done and how people lived their lives. ... When you look at art that's done in the field, someone was there, and someone was witness to that event."