QUANTICO, Virginia -- By next year, the population of combat wounded troops assigned to the Marines' Wounded Warrior Regiment will likely drop to zero.

But the unit has no plans to go out of business, Col. Scott Campbell, commander of the regiment, told Military.com in an interview. Rather, Campbell is overseeing a unit overhaul that includes a budget and staff reduction and a redesigned system for providing care that concentrates efforts on ill and injured troops least able to transition into civilian life without assistance.

Campbell was handpicked by then-commandant Gen. Joseph Dunford in early 2015 to bring cultural change to the Quantico-based regiment after the firing of its previous commander, Col. Shane "Rhino" Tomko.

Tomko, who had been accused of behaving inappropriately, embarrassing the unit at public functions, and sexually harassing subordinates, was ultimately convicted of driving drunk to his arraignment, sending inappropriate messages to a member of the unit, and illegal use of prescription drugs in May. He was sentenced to two months in the brig, and retired shortly after serving the time.

While Campbell took seriously his job to change the culture -- he says all the staff have heard him call sexual harassment a "death sentence" for those caught perpetrating it -- he quickly discovered that the problems at the unit extended beyond what was immediately apparent.

"It became clear to me that the regiment was very good at taking care of wounded, ill and injured, but in my opinion there was a lack of direction," he said. "And so, for me to get to know the organization and to right-size it like the commandant wanted, I just said, 'to heck with it, we're going to do a mission analysis.' We're going to do what I'm comfortable doing: going back to the basics and finding out where we're at from the troops to task all the different programs."

Activated in 2007 during the height of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, the demographics had shifted significantly since the days when Marine battalions would suffer dozens of serious combat wounds in a single deployment. With fewer deployments and a very limited number of troops in ground combat situations in Afghanistan and Iraq, the average Marine assigned to the unit was now more likely to be a cancer patient or the recipient of a head injury from a car crash than a combat amputee.

Unit Overhaul

The command was overstaffed and overfunded, Campbell found. And a number of the unit's regular activities, while good for its public image, failed to effectively help the wounded, ill and injured Marines assigned to the regiment.

For example, the Warrior Games, a massive, annual Olympics-style event involving all the military services, drew too much participation from veterans and not enough from actual members of the unit. And the unit's annual practice of calling all Marines who had received a Purple Heart, meaning they had been wounded in combat, was an ineffectively broad gesture, he found.

"That sounds great, that's a great bumper sticker," Campbell said. But, he added, the unit call center staff found themselves reaching out to general officers who had been wounded and recovered and moved on in their careers, rather than concentrating their efforts on the smaller number whose lives had been permanently changed by their injuries.

"Why don't we take that phone call and apply it to the guy who has [traumatic brain injury] and can't work, and call him every month," he said. "Or the double amputee, every other month. To check up on the guys who are most in need or mental health cases. So we reprioritized those phone calls from the call center and focused on those that really continue to need the help."

Campbell cut unit manning from 300 uniformed staff members to 175, most of whom are activated from the Marine Corps Reserve. He also trimmed about $4 million from the command's annual budget of roughly $20 million, he said. That's still a lot of money left in a Marine Corps scrimping to keep its aircraft flying and troops deploying, but Campbell said it pays to care for the 500 to 600 members of the regiment as well as an additional 400 outpatient Marines, and a call center that makes and fields tens of thousands of calls to troops in uniform as well as veterans.

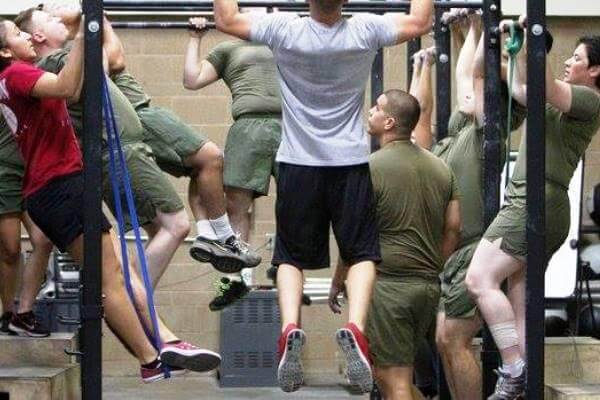

He brought the number of active-duty Wounded Warrior Regiment participants in the Warrior Games up from 56 percent to 85 percent between 2015 and this year, encouraging the regiment's East Coast and West Coast battalions to field participants with an eye to who would benefit most from competing in the games. For the unit's own Warrior Athlete Reconditioning Program, or WAR-P, he has launched a review of the sports Marines participate in. Perhaps, he suggested, wheelchair basketball is less relevant to today's unit members than it used to be.

A Perception Problem

Talk of getting rid of the Wounded Warrior Regiment as the wars drew down was short-lived, Campbell said. Marine Corps brass, he said, immediately realized that the unit could continue to serve a purpose as a safe place of recovery for ill and injured troops who needed intensive care and attention before they would be ready to return to their units, or transition to civilian life, as 97 percent of Marines assigned to the regiment eventually do.

The unit has become more selective: Campbell said it turns away about 30 percent of applicants, not because of any lack of combat connection, but because they're simply not complex enough to require the level of care that the regimental provides.

If a captain went out riding his bicycle and was hit by a car and broke his hip, he would not necessarily come here," he said. "Now if the captain was an alcoholic and had TBI during that accident and [post-traumatic stress disorder] and broke his hip, that's our kind of guy. We want to take the most complex, most difficult cases, take that burden off the fleet."

Currently, he said, about 2 percent of the Marines in the regiment are recovering from combat wounds. And for a nation accustomed to seeing ads depicting wounded warriors with visible combat scars--missing limbs, burns and bullet wounds--Campbell admits that there's a perception problem to overcome.

"We tell the truth," he said. "These young men and women who come to me, the vast majority of them are injured or become ill in the service of their country. It doesn't matter that they're not wounded … it's something I've brought up repeatedly at the Department of Defense when we discuss these things, making sure there's truth in advertising. There's nothing wrong with saying, this Marine hit a tree on a parachute accident preparing to deploy to defend our country. That's okay."

The War Plan

Part of Campbell's plan to adapt the Wounded Warrior Regiment for the future includes a war plan designed to rapidly expand unit staffing in the event the Marine Corps finds itself at the center of another major combat contingency. It leans heavily on reservists, who can be activated and deployed to meet staffing needs.

"It's odd for an organization for a regiment that doesn't have any guns, we have no radios, we have no tactical vehicles," he said. "We're going to have a daggone war plan."

And in the interim, Campbell fears the unit will continue to admit Marines suffering from unseen war wounds that are often felt months or even years after they return from the combat zone. Regiment leaders have found, he said, that episodes of post-traumatic stress are often triggered by a "catalyst," an unexpected or stressful life event that throws a service member off-balance and causes unresolved trauma to resurface. It's not clear, he said, when the "bow wave" of PTSD cases emerging in the fleet will subside.

"To say that the casualties are over, the unseen casualties of PTSD are not," he said. "I think we're going to deal with PTSD for awhile. You don't go to combat and lose friends without it affecting you."

--Hope Hodge Seck can be reached at hope.seck@military.com. Follow her on Twitter at @HopeSeck.